Prophetess of Health

Chapter 1: A Prophetess Is Born

By Ronald L. Numbers

"a true prophet"

J. N. Loughborough1

"a wonderful fanatic and trance medium"

Isaac C. Wellcome2

She was a mere child of not more than ten when a scrap of paper and a stone altered the course of her entire life. Walking to school one morning, Ellen Harmon spied a piece of paper lying by the wayside. Picking it up, the horrified little girl read that an English preacher was predicting the end of the world, perhaps in only thirty years. "I was seized with terror," she later wrote; "the time seemed so short for the conversion and salvation of the world." For several nights she tossed and turned, hoping and praying that she might be among the saints ready to meet Christ at his Second Coming.3 Little did she dream that for the next seventy-five years she would work and wait expectantly for her Savior's return.

Within a short time of this frightening episode, another incident nearly ended Ellen's life. With her twin sister, Elizabeth, and a friend, Ellen was passing through a public park when an older schoolmate, angry "at some trifle," hurled a rock at the girls. Ellen was struck squarely on the nose and knocked to the ground unconscious. For three weeks she lay in a stupor, oblivious to her surroundings, while friends and relatives sadly waited for her to die. When she finally regained her senses, she suffered not only acute physical pain but also anxiety over her prospects for salvation should she die.

Somehow she passed safely through the valley of death, but time never fully erased the traces of these two childhood experiences. For the remainder of Ellen's long life, good health and Christ's Second Coming were uppermost on her mind.

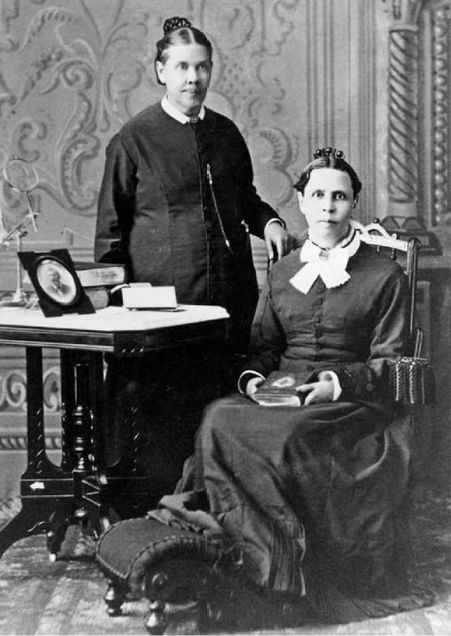

Ellen Gould Harmon and her sister, Elizabeth, were born on November 26, 1827, in the village of Gorham, Maine, a few miles west of Portland. Their father, Robert, a hatter of modest means, followed the common practice of having his children, six daughters and two sons, assist him in the home industry. Mother Eunice was a pious homemaker with strong theological convictions. When the twins were still preschoolers, the Harmon family moved into the city, where the girls eventually enrolled in the Brackett Street School.

Portland in the 1830s was a picturesque New England seaport with a population approaching fifteen thousand. Horse-drawn carts and carriages filled its famous tree-lined streets, and hoop-skirted ladies could still be seen on its crowded sidewalks. The city's location on a neck of land jutting into Casco Bay made it ideal for the West Indian maritime trade that supported the economy. Ships from Maine sailed to the south loaded with lumber or marine products and returned filled with sugar, molasses, rum, and other Caribbean goods. With so ready a supply of alcohol, it is not surprising that temperance became a burning local issue and that "intemperance" was a commonly cited cause of death. The greatest killers, however, were consumption, which accounted for over one-fourth of all mortality, and scarlet fever, which took another 20 percent. In religious matters, Portland had long been a Congregational stronghold, but Baptist and Methodist churches were beginning to attract sizable numbers.4

The Harmon family lived in the far southwestern outskirts of the city, not far from Ellen's school. Their neighbors on Spruce Street were working class or petty bourgeoisie. Among them were a merchant, a distiller, a truckman, a cordwainer, a shipcarpenter, a ropemaker, two stevedores, and a couple of laborers—the same type of hard-working people who later filled the Adventist ranks and became followers of Ellen White.5

It was in Portland, when Ellen was nine or ten, that the rock-throwing incident occurred. Despite the efforts of well-meaning physicians, Ellen's injuries continued to plague her for years. Her facial disfigurement—so bad that her own father could scarcely recognize her—caused frequent embarrassment and made breathing through her nostrils impossible for two years. Frayed nerves rebelled at simple assignments such as reading and writing. Her hands shook so badly she was unable to control her slate marks, and words became mere blurs on a page. Try as she might, she could not concentrate on her studies. Perspiration would break out on her forehead, and dizziness would overcome her.

The girl responsible for her suffering, now contrite and anxious to make amends, tried tutoring Ellen, but to no avail. Finally it became apparent to her teachers that she simply could not cope with schoolwork, and they recommended that she withdraw from classes. Later, in about 1839, she again attempted to resume her studies, at the Westbrook Seminary and Female College in Portland, but this, too, ended in disappointment and despair. "It was the hardest struggle of my young life," Ellen later lamented, "to yield to my feebleness, and decide that I must leave my studies, and give up the hope of gaining an education."

Her formal education ended, she resigned herself to the life of a semi-invalid, passing the time of day propped up in bed making hat crowns for her father or occasionally knitting a pair of stockings. In this way she could console herself with the knowledge that she was at least contributing to the family economy.

It is uncertain what effect, if any, her hat-making had upon her health. Some evidence suggests that about this time American hatters began using a mercury solution to treat the fur used in felt hats, a practice that frequently led to chronic mercurialism. This disease manifested itself in various psychic and physical disturbances: "abnormal degrees of irritability, excitability, irascible temper, timidity, depression or despondency, anxiety, discouragement without cause, inability to take orders, self-consciousness, desire for solitude, and excessive embarrassment in the presence of strangers." Tremor, making it difficult to control handwriting, was especially common. Hallucinations sometimes occurred in advanced cases. While it is impossible to know for sure if Ellen were exposed to mercury poisoning, and both unnecessary and unwise to assume that this malady would account for all of her unusual behavior, it might explain her trembling hands.6

Caught Up in the Millerite Delusion

In March, 1840, life took on new meaning for Ellen. In that month William Miller paid his first visit to the citizens of Portland to warn them of Christ's soon return. Miller, a captain in the War of 1812, retired from the army in 1815 to take up farming in Low Hampton, New York. A decade or so earlier he had abandoned Christianity for deism, but growing concern about his fate after death drove him to intense Bible study and a return to the faith of his youth. His interest focused on the biblical prophecies, particularly Daniel 8:14: "Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed." On the assumption that each prophetic day represented a year, that the cleansing of the sanctuary coincided with the Second Coming of Christ, and that the 2300 years began in 457 B.C., when Artaxerxes of Persia issued a decree to rebuild Jerusalem, Miller concluded that events on this earth would terminate "about the year 1843."7

For thirteen years Miller kept his views largely to himself, but as the end inexorably approached, he could no longer remain silent. In the summer of 1831, at the age of forty-nine, he took to the pulpit; two years later the Baptists granted him a license to preach. By mid-1839 he had delivered over eight hundred lectures in towns throughout New York and New England. His disturbing message often held audiences for prolonged periods, but aside from his earnestness and gravity he was an undistinguished speaker. "There is nothing very peculiar in the manner or appearance of Mr. Miller," wrote the editor of a Massachusetts newspaper. "Both are at least to the style and appearance of ministers in general. His gestures are easy and expressive, and his personal appearance every way decorous. His Scripture explanations and illustrations are strikingly simple, natural, and forcible...."8

During the early years of his ministry Miller made no attempt at organization and limited his preaching to the small churches that invited him. This changed in 1840 when Joshua V. Himes, the energetic young pastor of the Chardon Street Chapel in Boston, teamed up with Miller to coordinate a national crusade, with Himes assuming responsibility for organization and publicity. At the peak of the movement about two hundred ministers and five hundred public lecturers were spreading the Millerite message, and an estimated fifty thousand believers were waiting expectantly for their Savior's return.9

Little is known about the social characteristics of these Millerites, but one historian has recently concluded that, unlike other apocalyptic millenarians, "They do not seem to have been people deprived of power, nor potential revolutionaries, nor, most significantly, threatened with destruction." Many, including Miller and Himes, were respected and influential members of their communities. Nevertheless, the Millerites were acutely aware of social unrest and religious apostasy, which they interpreted to be signs of the end. In contrast to the optimistic postmillennialists, like the popular evangelist Charles G. Finney, who expected soon to usher in a thousand years of peace and prosperity, the pessimistic Millerites saw only evidence of a world in decay.10

What they did share with the postmillennialists was a fondness for enthusiastic revivals and camp meetings, with emotional sermons, spirited songs, and fervent prayers. The Millerites held their first camp meeting in the summer of 1842 in East Kingston, New Hampshire, near the home of Ezekiel Hale, Jr., a friend of Sylvester Graham's who took care of local arrangements. A chance visitor, John Greenleaf Whittier, described the event, which attracted between ten and fifteen thousand individuals:

Three or four years ago [he wrote in 1845], on my way eastward, I spent an hour or two at a camp-ground of the Second Advent in East Kingston. The spot was well chosen. A tall growth of pine and hemlock threw its melancholy shadow over the multitude, who were arranged upon rough seats of boards and logs. Several hundred—perhaps a thousand people were present, and more were rapidly coming. Drawn about in a circle, forming a background of snowy whiteness to the dark masses of men and foliage, were the white tents, and back of them the provision-stalls and cook-shops. When I reached the ground, a hymn, the words of which I could not distinguish, was pealing through the dim aisles of the forest. I could readily perceive that it had its effect upon the multitude before me, kindling to higher intensity their already excited enthusiasm. The preachers were placed in a rude pulpit of rough boards, carpeted only by the dead forest-leaves and flowers, and tasselled, not with silk and velvet, but with the green boughs of the sombre hemlocks around it. One of them followed the music in an earnest exhortation on the duty of preparing for the great event. Occasionally he was really eloquent, and his description of the last day had the ghastly distinctness of Anelli's painting of the End of the World.

Suspended from the front of the rude pulpit were two broad sheets of canvas, upon one of which was the figure of a man, the head of gold, the breast and arms of silver, the belly of brass, the legs of iron, and feet of clay, the dream of Nebuchadnezzar. On the other were depicted the wonders of the Apocalyptic vision,—the beasts, the dragons, the scarlet woman seen by the seer of Patmos, Oriental types, figures, and mystic symbols, translated into staring Yankee realities and exhibited like the beasts of a travelling menagerie. One horrible image, with its hideous heads and scaly caudal extremity, reminded me of the tremendous line of Milton, who, in speaking of the same evil dragon describes him as 'swinging the scaly horrors of his folded tail.'

"The white circle of tents; the dim wood arches; the upturned, earnest faces; the loud voices of the speakers burdened with the awful symbolic language of the Bible; the smoke from the fires, rising like incense"—all left an indelible impression on the poet and presumably struck fear in the hearts of many who attended this and similar meetings.11

According to Ellen White, "Terror and conviction spread through the entire city" of Portland during Miller's 1840 visit. Believers and skeptics alike packed into the Casco Street Christian Church to hear his strange but plausible interpretations of Bible prophecy. News of Father Miller's lectures again caused fear to well up in Ellen's heart as it had that day about four years earlier when she picked up the scrap of paper announcing the impending end of the world. Yet she wanted to hear what the farmer-preacher had to say. Accompanied by several friends, Ellen made her way to the Casco Street Church and took her place among the crowds of listeners who filled the sanctuary. When Miller invited sinners to step forward to the "anxious seat," Ellen, under conviction, pressed through the congested aisles to join the "seekers" at the front. Still, she was not comforted, and doubts of her unworthiness haunted her day and night.

In the summer of 1841 she traveled with her parents to a Methodist camp meeting in Buxton. Here the constant exhortations to godliness only heightened her sense of sinfulness. In desperation one day she fell before the altar and pleaded for God's mercy. There, kneeling and praying, her burden of guilt suddenly vanished. The dramatic change in her countenance moved a lady nearby to exclaim, "His peace is with you, I see it in your face!" To Ellen, the whole earth now "seemed to smile under the peace of God."

Upon returning home, she decided to join her parents' Chestnut Street Methodist Church and requested baptism. After a probationary period, during which William Miller returned to Portland for a second series of lectures and reawakened Ellen's interest in the Second Advent, she and eleven other candidates were immersed in the waters of Casco Bay. On June 26, 1842, with the wind blowing and the waves running high, she symbolically buried her sins in the watery grave. She emerged from the bay emotionally spent: "When I arose out of the water, my strength was nearly gone, for the power of God rested upon me. Such a rich blessing I never experienced before. I felt dead to the world, and that my sins were all washed away."

But her beautiful day was nearly ruined in only a few hours when she went to the church to receive the official welcome into membership. There, standing next to the plainly dressed Ellen, was another candidate decked out in gold rings and a fancy bonnet. To Ellen's dismay, her minister, the Reverend John Hobart, went right on with the service without so much as mentioning the offending adornments. This experience proved to be a great trial to young Ellen, whose faith in the popular churches was already being shaken.

Even her conversion and baptism failed to bring lasting peace to Ellen's troubled mind. At times she became discouraged and sank into deep despair. With sins so grave as hers, she felt certain no forgiveness could be granted. Sermons vividly depicting the red-hot flames of hell only intensified her torment and pushed her closer to the breaking point. "While listening to these terrible descriptions, my imagination would be so wrought upon that the perspiration would start, and it was difficult to suppress a cry of anguish, for I seemed already to feel the pains of perdition."

In addition, she began experiencing terrible feelings of guilt over her timidity to witness publicly for Christ. She especially wanted to participate in the small Millerite prayer services but feared her words would not come out right. Her burden of guilt grew to such proportions that even her secret prayers seemed a mockery to God. For weeks depression engulfed her. At night she would wait until Elizabeth had fallen asleep, then crawl out of bed and silently pour out her heart to God. "I frequently remained bowed in prayer nearly all night," she wrote, "groaning and trembling with inexpressible anguish, and a hopelessness that passes all description."12

While in this state of mind she began having religious dreams similar to those that followed her through life. In the first one recorded she saw herself failing to gain salvation, prevented by pride from humbling herself before "a lamb all mangled and bleeding." She awoke certain that her fate had been sealed, that God had rejected her. But then she had a second dream. In this Jesus touched her head and said, "Fear not." Filled with renewed hope, Ellen at last confided in her mother, who advised talking things over with Elder Levi Stockman, a local Methodist minister who had become a Millerite. With tears in his eyes he listened to her unusual story and then said, "Ellen, you are only a child. Yours is a most singular experience for one of your tender age. Jesus must be preparing you for some special work."

Although encouraged by Elder Stockman's words, Ellen continued to brood over her inability to pray publicly. One evening during a prayer meeting in the home of her uncle Abner Gould, she determined to break her silence. While the others prayed, she knelt, trembling, waiting her chance. Then before she really knew what was happening, she, too, was speaking. As the pent-up words spilled out, she lost touch with the world and collapsed on the floor. Those around her suggested calling a physician, but Ellen's mother assured the group that it was "the wondrous power of God" that had prostrated her daughter. Ellen herself said, "The Spirit of God rested upon me with such power that I was unable to go home that night." The next day she left her uncle's home a changed person, full of peace and happiness, and for six months she was in "perfect bliss."

Public Ministry Commences

Ellen launched her public ministry the night following her prayer-meeting victory. Before a congregation of Millerite believers she tearfully related her recent experience. All fear disappeared as she spoke, and before long she "seemed to be alone with God." Soon she received an invitation to speak at the Temple Street Christian Church, where her story again moved many in the audience to weep and praise God. Ellen also began holding private meetings with her friends, who she feared were not ready to meet the Lord. At first some questioned her childish enthusiasm and ridiculed her experience, but eventually she converted every one of them. Often she would pray till nearly dawn for the salvation of a lost friend, before drifting off to sleep and dreaming of another in spiritual need.

As the Millerite movement gathered momentum, more and more of its followers found themselves in doctrinal conflict with their local churches. The Harmon family was no exception. By 1843 hostility had grown to the point where members would groan audibly when Ellen got up to speak in class meetings; so she and her teen-age brother, Robert, quit attending. Finally the Reverend William F. Farrington, pastor of the Chestnut Street Methodist Church, called on the family to inform them that their divergent teachings would no longer be tolerated. He suggested that they quietly withdraw from the church and thus avoid the publicity of a trial. Mr. Harmon, seeing no reason to be ashamed of his beliefs, demanded a public hearing. Here charges of absenteeism from class meetings were brought against the Harmons, and the following Sunday seven members of the family—including Ellen—were formally dismissed from the Methodist church.

Excitement and anticipation mounted as the months and days of 1843 slipped by. Throughout March a brilliant comet hovered in the southwestern sky, like a heavenly messenger announcing the impending end of the world. Although Father Miller would say only that he expected the Lord to come sometime during the Jewish year extending from March 21, 1843, to March 21, 1844, less cautious men were all too willing to provide the faithful with specific dates for the great event. A favorite of many was April 14, the beginning of Passover and the anniversary of Christ's crucifixion. With the passing of each appointed time, a new wave of disappointment spread through the Millerite camp, allegedly driving some distraught souls to suicide or insanity.13

In Ellen's hometown of Portland the Millerites gathered nightly in Beethoven Hall to renew their courage and to make a final appeal to the still unconverted. Often these sessions continued late into the night as one after another Spirit-filled Millerite rose to give a spontaneous "exhortation." One evening Ellen watched in awe as the Reverend Samuel E. Brown, moved by a colleague's testimony, suddenly turned porcelain white and fell from his chair on the platform. In a few minutes, after regaining his composure, he stood up and with his face "shining with light from the Sun of Righteousness" gave what Ellen thought was "a very impressive testimony." As they made their way home through the darkened streets of the city, the Millerites filled the night air with joyful shouts of praise to God, undoubtedly much to the annoyance of nearby sleeping residents.14

Disappointment

March 21, 1844, came and went with no sign of Christ's appearance. Obviously a mistake had been made, and on May 2, William Miller confessed that his prophetic calculations had been in error. At the same time he reassured his followers that he still believed the Second Coming was not far off. While some of the faint-hearted now deserted the movement, a surprising number, including most of the Millerite leaders, adopted an exegetical solution offered by Samuel S. Snow, a Congregational-Millerite preacher. According to Snow, a correct reading of the prophecy in Daniel upon which Miller had based his dates indicated that Christ would not come until the "tenth day of the seventh month" of the Jewish calendar, that is, October 22, 1844. Renewed energy surged through the Millerite ranks. By mid-August all hopes were pinned on October 22. No sacrifice—family, job, or fortune—seemed too great, for time on this earth would soon end. For Ellen, this was the happiest period of her life. Free from discouragement, she went from home to home earnestly praying for the salvation of those whose faith was wavering, or retired with friends to a secluded grove for quiet seasons of prayer.15

Few today can imagine the bitter disappointment of those devout Millerites who watched in vain through the night of October 22 for their Savior's appearance. Hiram Edson, a farmer in upstate New York, recorded those agonizing hours. He and his friends had waited hopefully until midnight, then burst into uncontrollable sobs. "It seemed that the loss of all earthly friends could have been no comparison. We wept, and wept, till the day dawn." Millerite reactions varied from resentment to puzzlement. Some bitterly renounced their former hopes in the Second Coming as a cruel delusion. Others, including a large group led by Miller and Himes, admitted their mistake but nevertheless clung to the certainty of Christ's soon return. But a resolute few insisted that their sacrifices had not been in vain, that an event of cosmic significance had taken place on October 22.16

This was the position of Hiram Edson. Early in the morning after the disappointment, he and some Millerite brothers had gone out to a barn to plead with God for an explanation. Their prayers were not long in being answered. After breakfast, while passing through a nearby field, Edson had a vision of heaven. He saw that the cleansing of the sanctuary foretold in Daniel 8:14 did not coincide with the Second Coming but rather with Christ's entry into the most holy place of the heavenly sanctuary just prior to his return. This view was taken a step farther by two Millerite preachers, Apollos Hale and Joseph Turner, in a paper called the Advent Mirror, published in January, 1845. According to Hale and Turner, Christ had ended his ministry for the world on October 22 and, upon entering the most holy place of the sanctuary, had shut the "door of mercy" on those who had rejected the Millerite warning.17

"Visions"

On a wintry day in December, 1844, seventeen-year-old Ellen Harmon met with four friends in the Portland home of a Mrs. Haines to pray for divine guidance. As the women knelt in a circle, the "Holy Spirit" rested upon Ellen in a new and dramatic way. Bathed in light, she seemed to be "rising higher and higher, far above the dark world." From her vantage point she saw the Advent people traveling a straight and narrow path toward the New Jerusalem, their way lighted by the October 22 message. When some "rashly denied the light behind them, and said that it was not God that had led them out so far," they stumbled in the darkness and fell to "the wicked world below which God had rejected." The meaning of her vision was clear: October 22 had been no mistake; only the event had been confused.18

The following February, while visiting in Exeter, Maine, Ellen received a second vision on the importance of October 22. Subsequent to the publication of the Advent Mirror, dissension had arisen among the Exeter Millerites over the shut-door question. Had God really closed the door of salvation to sinners on October 22? As Ellen sat listening to an Adventist sister express her doubts on the shut door, a feeling of intense agony came over her and she fell from her chair to the floor. While others in the room sang and shouted, the Lord showed Ellen that the door had indeed been closed. Most of those who witnessed this apparently heaven-sent answer "received the vision, and were settled upon the shut door." Within a day or so Ellen discussed what she had seen with Joseph Turner and was overjoyed to discover that he, too, had been proclaiming the same view. Although his Advent Mirror had been in the house where she was staying, she said that she had never seen a word of it prior to her vision.19

Joseph Bates

In the spring of 1846 Ellen met a retired sea captain named Joseph Bates, who had broken with his former Millerite brethren and was now observing the seventh-day Sabbath. At first the wary Bates doubted Ellen's reputed visionary experiences, but in November a special vision on astronomy, a favorite subject of his, won him over completely. In his presence Ellen described various details of the solar system and the so-called gap in the constellation Orion, then a topic of great interest because of the telescopic observations of William Parsons, the third earl of Rosse. Just months earlier, Bates himself had written a tract, "The Opening Heavens," relating Lord Rosse's discoveries, but Ellen assured him she had had no prior knowledge of astronomy.20

The captain's faith in the young prophetess was doubly strengthened when she had another vision, giving divine sanction to his views on the Sabbath. In heaven, she said, Jesus had allowed her to see the tables of stone on which the Ten Commandments were inscribed. To her amazement, the fourth commandment, requiring observance of the seventh day, was "in the very center of the ten precepts, with a soft halo of light encircling it." An angel kindly explained to the puzzled young woman that the Millerites must begin keeping the "true Sabbath" before Christ would come. By embracing the seventh-day Sabbath and making it a new "test," Ellen placed herself in direct opposition to the moderate wing of Millerites, who at the Albany (New York) Conference of April, 1845, had officially condemned the doctrines Ellen had come to represent: visions, the shut door, and the seventh-day Sabbath. For the next few years she and the small band of fellow believers, generally drawn from Millerites with little formal education, were designated the "sabbatarian and shut-door" Adventists.21

Prophets Galore

To most Millerites, Ellen's visions were simply another manifestation of the unfortunate religious drift of the times toward "fanaticism." Early nineteenth-century America abounded with "prophets" of every description, from little-known frontier seers in Ellen Harmon's own Methodist church to prominent sectarian leaders. Mother Ann Lee of the Shakers had long since passed away, but her devoted followers perpetuated her reputation as the female Messiah. In the 1830s an epidemic of visions spread through the Shaker communes as young girls "began to sing, talk about angels, and describe a journey they were making, under spiritual guidance, to heavenly places." Frequently those afflicted "would be struck to the floor, where they lay as dead, or struggling in distress, until someone near lifted them up, when they would begin to speak with great clearness and composure." Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend who founded the religious community of Jerusalem in western New York, was known for her visions and religious dreams. Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet from Palmyra, New York, began having visions at age fourteen and continued to receive divine revelations until his death in 1844. During the second quarter of the century the Mormons were highly visible in Missouri and Illinois, and when Ellen White went west in the 1850s, she was often mistaken for a Mormon.22

Even the Millerite movement in its final days was so infected with religious enthusiasm that Joshua V. Himes complained of being in "mesmerism seven feet deep."23 The most notorious case was that of John Starkweather, assistant pastor of Himes's Chardon Street Chapel, whose "cataleptic and epileptic" fits greatly embarrassed his more subdued colleagues. Eventually he was expelled from the chapel when his spiritual gifts proved to be contagious. Despite the best efforts of Father Miller—who himself had religious dreams—to maintain decorum, his followers often got so emotionally worked up that their meetings seemed to him "more like Babel, than a solemn assembly of penitents bowing in humble reverence before a holy God."24

Fanaticism continued to plague the Millerites even after the October 22 disappointment, and it seemed to be particularly prevalent among shut-door believers. In Springwater Valley, New York, a black shut-door advocate named Houston set up a commune called the Household of Faith and the Household of Judgment and declared that "Jesus Christ in him was judging the world." At times God spoke directly to him in visions—"no vain imagination of a crazy mind," he assured William Miller—but his authoritarian manner, irrational acts, and practice of "spiritual wifery" soon alienated even his most ardent supporters.25 The shut-door group in Portland, Maine, was even more notorious in Millerite circles for its "continual introduction of visionary nonsense," as Himes called it. In March of 1845 Himes informed Miller that a Sister Clemons of that city "has become very visionary, and disgusted nearly all the good friends here." But only a couple of weeks later he reported that another Portland sister had received a vision showing that Miss Clemons was of the Devil. "Things are in a bad way at Portland," he concluded.26

Ellen Harmon may not have been involved in these episodes, but she could hardly have been unaware of them. And there were at least two persons she met in Maine whom she regarded as authentic prophets. As a girl in the early 1840s she had gone with her father to Beethoven Hall to hear a tall, light-skinned mulatto named William Foy relate his "extraordinary visions of another world." Reputable Millerites testified to his genuineness, and a physician who examined him during one of his trances found no "appearance of life, except around the heart." After the Great Disappointment, Foy turned out one evening to hear Ellen give her testimony. While she was speaking, he began jumping up and down, praising the Lord, and insisting that he had seen exactly the same things. Ellen took this as an indication that God had chosen her as Foy's replacement.27

Closer to home was Ellen's relationship with Hazen Foss, her sister Mary's brother-in-law and the brother of her dear friend Louisa Foss. Shortly before October 22, 1844, Hazen had received a vision similar to Foy's, which the Lord had instructed him to relate to others. However, after the disappointment he became bitter and refused to carry out his duty. If he said anything to his family about his experience, it seems likely that Ellen learned of it by the time she had her first vision; but apparently she did not talk with him until after her third one, when she visited Mary and Samuel Foss in Poland, Maine. In the course of their long conversation Hazen told Ellen the Lord had warned him that the light would be given to someone else if he refused to share it. Upon hearing Ellen's story, he reportedly said to her, "I believe the visions are taken from me, and given to you." He died an atheist.28

Physically and conceptually Ellen's early visions closely resembled those of her contemporaries Foy and Foss. The episodes were unpredictable; she might be praying, addressing a large audience, or lying sick in bed, when suddenly and without warning she would be off on "a deep plunge in the glory."29 Often there were three shouts of "Glory! G-l-o-r-y! G-l-o-r-y!"—the second and third "fainter, but more thrilling than the first, the voice resembling that of one quite a distance from you, and just going out of hearing." Then, unless caught by some alert brother nearby, she slowly sank to the floor in a swoon. After a short time in this deathlike state, new power flowed through her body, and she rose to her feet. On occasion she possessed extraordinary strength, once reportedly holding an eighteen-pound Teale Bible in her outstretched hand for one-half hour.30

During these trances, which came five or ten times a year and lasted from a few minutes to several hours, Ellen frequently described the colorful scenes she was seeing. One eyewitness recalled that

She often uttered words singly, and sometimes sentences which expressed to those about her the nature of the view she was having, either of heaven or of earth. . . . When beholding Jesus our Saviour, she would exclaim in musical tones, low and sweet, "Lovely, lovely, lovely," many times, always with the greatest affection. . . . Sometimes she would cross her lips with her finger, meaning that she was not at that time to reveal what she saw, but later a message would perhaps go across the continent to save some individual or church from disaster. . . . When the vision was ended, and she lost sight of the heavenly light, as it were, coming back to the earth once more, she would exclaim with a long drawn sigh, as she took her first natural breath, "D-a-r-k." She was then limp and strengthless, and had to be assisted to her chair....31

According to the testimony of numerous physicians and curiosity seekers, her vital functions slowed alarmingly, with her heart beating sluggishly and respiration becoming imperceptible. Although she was able to move about with complete freedom, not even the strongest men could forcibly budge her limbs. On occasion she was subjected to indignities. For example, her husband, James White, let one young man—later a leading Adventist minister—see if she could survive for ten minutes while he simultaneously pinched her nose and covered her mouth.32 Many visions left Ellen in total darkness for short periods, but usually her eyesight returned to normal after a few days.

The cause of her visions was a matter of dispute. Both she and her followers considered them genuine revelations from God, identical in nature to those of the biblical prophets. But skeptics offered various other explanations. Many attributed them to mesmerism, or hypnotism, which her friends attempted to refute by pointing out that "she has a number of times been taken off in vision, when in prayer alone in the grove or in the closet." Some physicians diagnosed her condition as hysteria, an ill-defined disease known sometimes to produce deathlike trances and hallucinations, especially in women. The two Kellogg doctors, Merritt and John, believed she suffered from catalepsy, which, as the latter described it, "is a nervous state allied to hysteria in which sublime visions are usually experienced. The muscles are set in such a way that ordinary tests fail to show any evidence of respiration, but the application of more delicate tests show that there are slight breathing movements sufficient to maintain life. Patients sometimes remain in this condition for several hours."33

A special angel always guided Ellen on her heavenly tours, directing her attention to events past and future, celestial and terrestrial. Today her descriptions of the other world might seem somewhat fanciful, but to her literalistic nineteenth-century followers they had the familiar ring of truth. Her verbal portrait of Satan, for example, was not unlike those that had terrified her as a church-going child:

I was then shown Satan as he was, a happy, exalted angel. Then I was shown him as he now is. He still bears a kingly form. His features are still noble, for he is an angel fallen. But the expression of his countenance is full of anxiety, care, unhappiness, malice, hate, mischief, deceit, and every evil. That brow which was once so noble, I particularly noticed. His forehead commenced from his eyes to recede backward. I saw that he had demeaned himself so long, that every good quality was debased, and every evil trait was developed. His eyes were cunning, sly, and showed great penetration. His frame was large, but the flesh hung loosely about his hands and face. As I beheld him, his chin was resting upon his left hand. He appeared to be in deep thought. A smile was upon his countenance, which made me tremble, it was so full of evil, and Satanic slyness. This smile is the one he wears just before he makes sure of his victim, and as he fastens the victim in his snare, this smile grows horrible.34

Not all of Ellen's revelations were accompanied by physical manifestations. She often had dreams at night, especially as she grew older, which she thought were as much inspired as her daytime visions. Naturally some skeptics suspected that her dreams might not be very different from their own, but she assured them that she could tell when her dreams were of divine origin: "the same angel messenger stands by my side instructing me in the visions of the night, as stands beside me instructing me in the visions of the day."35 Unlike the angel Moroni who appeared to the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, Ellen's heavenly visitor never seems to have identified himself by name.

The reception of her heavenly messages was only the first step in the line of communication from God to the Advent believers. Either orally or in writing, these had to be relayed to those for whom they were intended. Ellen steadfastly claimed that in this work she did not rely on her own faulty memory. Whenever a previous revelation was needed, the scenes she might have seen years before would come to her "sharp and clear, like a flash of lightning, bringing to mind distinctly that particular instruction." She professed to be "just as dependent upon the Spirit of the Lord in relating or writing a vision, as in having the vision. It is impossible for me to call up things which have been shown me unless the Lord brings them before me at the time that he is pleased to have me relate or write them." In this way she was able to guarantee that her words of counsel came free from any contaminating earthly influences.36

In her second vision, late in 1844, Ellen had been told that part of her work as God's messenger would be to travel among the scattered flock of Millerites, relating what she had seen and heard. The task might be painful at times, but God would see her through the ordeal. Although somewhat shy, Ellen was not embarrassed by her assignment. Religious work was socially acceptable for a young woman, and she was not without personal ambition. Indeed, she feared that her new responsibility might make her proud. But when an angel assured her that the Lord would preserve her humility, she determined to carry out his will. Only one obstacle stood in her way: the need for a traveling companion. Since her childhood accident, her health had never been good. At five feet, two inches, and barely eighty pounds, she was literally skin and bones. Lately an attack of "dropsical consumption" had damaged her lungs and made breathing difficult. Fatigue from long trips on steamboats and railway cars frequently brought on dangerous fainting spells, during which she might remain breathless for minutes. Obviously she could not travel alone, but who would go with her? Robert, her closest brother, was himself too feeble to be of much assistance and seemed to be self-conscious of his sister's gift. Mr. Harmon had too many mouths to feed at home even to consider chaperoning his daughter on her travels.37

Her hopes thus thwarted, Ellen once again sank into depression and wished to die. Then a miracle happened. One evening, while prayer was being offered in her behalf, "a ball of fire" struck her over the heart, knocking her to the floor helpless. As the dark cloud of oppression rolled away, an angel repeated her commission: "Make known to others what I have revealed to you." Ellen now knew that God would somehow find a way.38

Her first opportunity to travel came almost providentially a short time later when Samuel Foss, her brother-in-law, offered to take her to visit her sister in Poland, Maine. Thankfully she accepted this chance to give her testimony, despite her inability for the past months to speak above a whisper. Her faith was rewarded. As she related her experience to the small band of Poland Adventists, her voice cleared up perfectly. Soon she was traveling throughout New England accompanied by her sister Sarah or by Louisa Foss, the sister of Samuel and Hazen—exhorting the disappointed Millerites to hold fast for the Lord was coming soon.39

Doubts and Doubters

One of Ellen's greatest trials as she went from place to place was the oft-repeated suggestion that her trances were mesmeric in origin. Mesmerism, or animal magnetism, originated in Germany in the 1770s with Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer's "discovery" of an invisible fluid, like electricity, that coursed through the human body. According to Mesmer, obstructions to the flow of this animal magnetism caused disease, which could be cured by the magnetic emanations from another person's hands or eyes. This treatment often put the subject in a deep trance, with unpredictable and sometimes entertaining results. Mesmer's novel therapy attracted little American interest until 1836, when a French medical school dropout named Charles Poyen landed in Portland and began lecturing, with notable success, on the topic. Among his converts was Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, mentor of Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science. By the early 1840s traveling mesmerists were a popular attraction throughout New England, and Boston alone claimed "two or three hundred skilful [sic] magnetizers."40

At times even Ellen was plagued with doubts about the nature of her revelations. Were they possibly the effect of mesmerism or, worse yet, a Satanic delusion? She was somewhat comforted by her discovery that the visions continued even when she retreated to a secluded spot away from any human influence. But the doubts continued to haunt her. One morning as she knelt for family prayers, she felt a vision coming on. For an instant she wondered if this could be a mesmeric force and was immediately struck dumb. As divine punishment for questioning, she was unable to utter a word for twenty-four hours and had to communicate by means of a pencil and slate. There was a hidden blessing in this experience; to her great delight, she was now able for the first time since her childhood accident to hold a writing instrument without shaking. The next day her speech returned, and never again did Ellen doubt the source of her visions.41

Her critics were not so easily silenced. Joseph Turner, with whom she had previously shared her views on the shut door, was among those convinced that mesmerism accounted for her strange behavior. He felt sure that, given the opportunity, he could put her in a mesmeric trance and control her actions. He soon had his chance when Ellen again visited her sister in Poland. While Ellen described what her angel had recently shown her, Turner sat nearby intently staring at her eyes through his spread fingers, hoping in this way to bring her under his hypnotic power. In the midst of her testimony Ellen sensed "a human influence" being exerted against her and remembered God's promise to send a second angel if ever she were in danger of falling under an earthly influence. Raising her arms heavenward, she cried, "Another angel, Father! Another angel!" At once she was freed from Turner's sinister power and went on speaking in peace. Her contemporary Mrs. Eddy was less successful in dealing with malicious animal magnetism—M.A.M. she called it—and repeatedly went to great lengths to protect herself from its influence.42

James White

During a trip to eastern Maine in 1845 Ellen struck up a friendship with a twenty-three-year-old Millerite minister named James White, whom she had casually met sometime earlier in Portland. He was six years her senior, but the two young Adventists soon discovered they had much in common. Like Ellen, James came from a large New England family, being the fifth of nine children. He, too, had been a sickly child, with such poor vision that he had been unable to attend school until nineteen years of age. Then in twelve weeks of intensive study at St. Albans Academy he had obtained a teaching certificate.43

In September, 1842, after teaching school off and on for a couple of years and spending another seventeen weeks in attendance himself, James White listened to Miller and Himes speak at a camp meeting and soon afterward abandoned the classroom to become a full-time Millerite preacher (with credentials from the Christian Connection, the church of his parents). Borrowing a horse from his father and worn-out saddle and bridle from a minister friend, he set out that first winter "thinly clad, and without money." His assets consisted of a cloth chart illustrating the biblical prophecies, three prepared lectures, a strong voice, and plenty of determination. By April he had traveled hundreds of miles; his horse was ill, his clothes were worn, and he was still penniless. Yet he continued to proclaim the Millerite message, displaying the perseverance and fortitude that would serve him so well during the formative years of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Though apparently successful as a Millerite evangelist, young White never occupied a prominent or influential position in the movement.44

It did not take James long to become a firm believer in Ellen's supernatural powers or to see the dangers of her traveling unescorted. Several times during her early ministry, warrants had been issued for her arrest, and hostile groups occasionally threatened her. As James saw it, it was "his duty" to accompany Ellen on her visits to the widely scattered Adventists of New England. Mrs. Harmon, however, saw it differently. When she got wind of the arrangement, she immediately ordered her daughter home in hopes of sparing her reputation. But James and Ellen were not to be separated, and before long they were back on the road with their friends, contacting the faithful in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. With Christ coming in such a short time—possible dates were still being suggested—marriage seemed out of the question. James looked upon the idea as "a wile of the Devil" and warned another couple contemplating such a move that they would be denying their faith in the Second Coming. Unfortunately, some people misunderstood the innocent relationship between James and Ellen, and ugly rumors began to circulate. It was clear, said James to Ellen one day, that "something had got to be done." So on August 30, 1846, they set their reservations aside and presented themselves before a Portland justice of the peace to become man and wife.45

Married life for the newlyweds was far from glamorous. Since James's ministry did not provide him with a steady income, the nearly destitute couple was forced to move in with the Harmons, who had returned to Gorham. Here the Whites set up headquarters for about a year, until after the birth of their first child, Henry, in August, 1847. About this time an Adventist family from Topsham, Maine, the Stockbridge Howlands, took pity on the struggling young prophetess and her husband and invited them to occupy a rent-free room upstairs in their home. The Whites gratefully accepted the offer and with borrowed furniture set up housekeeping in Topsham. James put in long hours hauling rock or chopping cordwood at fifty cents a day, and with assistance from the Howlands he managed to keep food on the table. These trials and tribulations were heaven sent, the Lord explained to Ellen, to keep them from settling down to a life of ease.46

Before little Henry reached his first birthday, his parents reluctantly decided to leave him with friends and become itinerant preachers. The separation nearly broke Ellen's heart, but she vowed not to let her motherly affection keep her "from the path of duty." For four years, from 1848 to 1852, the Whites crisscrossed New England and New York, preaching their "sabbath and shut-door" message and living from hand to mouth on the meager contributions of their Adventist supporters. For lack of money, they "traveled on foot, in second-class cars, or on steamboat decks." The arrival of their second son, James Edson, in the summer of 1849 brought only a brief interruption to their nomadic life. He, too, was left while still a baby with a kind Millerite sister in Oswego, New York.47

No doubt encouraged by the more literate James, Ellen began in 1846 to publish her visions. Already one of her revelations had appeared unexpectedly in a Cincinnati paper, the Day-Star, edited by Enoch Jacobs, who later led a small group of Millerite defectors into a Shaker commune. Ellen had written him a private letter describing her first vision, which to her surprise he had published. It was apparent that the only way to control what got printed was for the Whites to do it themselves. So as they traveled about the country, Ellen would write out as best she could what she had seen, and then James would carefully go through the manuscript, correcting grammar and polishing style, until it came up to his standards for publication. Some critics suspected James contributed more than his editorial talents to the production of Ellen's testimonies, but she always insisted that only God influenced the content. By 1851 the Whites had turned out three broadsides and a small pamphlet and had launched a succession of periodicals culminating in the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald.48

The Shut Door Debacle

The year 1851—seven years after the Great Disappointment—had special meaning for the sabbatarians. For some time Joseph Bates had been suggesting that this might be the year of their Savior's return. Early in 1849 Ellen had warned against thinking that time might "continue for a few years more," and in June of the following year her angel informed her that "Time is almost finished." The doctrines she and James had thoughtfully studied out over the past several years would now have to be learned by others "in a few months." But again Christ did not appear. Surely the Whites, who had sacrificed so much, could not be blamed for his delay. In Ellen's mind the responsibility rested squarely on the shoulders of those Millerites who, at the Albany Conference of 1845, failed to endorse the seventh-day Sabbath and visions like her own.49

By 1851 the Whites had abandoned much of their shut-door doctrine. They would still grant no opportunity for salvation to those who had heard and rejected the 1844 message, but they allowed the door might be cracked sufficiently to permit the entrance of children, Millerites who were willing to accept the seventh-day Sabbath, and a few other honest-hearted souls who had not rejected the October 22 message. The problem was what to do with all of Ellen's inspired testimonies indicating the door of mercy had been shut. In an attempt to take care of this embarrassment, she and James collected her early writings, systematically deleted passages that might be construed as supporting the shut door, and published the edited version as Ellen's first book, A Sketch of the Christian Experience and Views of Ellen G. White (1851). From then on the Whites publicly denied that Ellen had ever been shown that the door was shut, although James apparently admitted on occasion that perhaps young Ellen had been unduly influenced by shut-door advocates at the time of her first vision.50

A crisis over Ellen's visions also developed in 1851. In July she wrote her friends, the Dodges: "The visions trouble many. They [know] not what to make of them." The causes for this dissatisfaction are complex. Among the sabbatarian Adventists, some were doubtless puzzled by her changing stand on the shut door, while others resented her habit of publishing private testimonies revealing their secret sins and names. Nonbelievers frequently charged that the visions were being elevated above the Bible. This criticism particularly galled James. In an effort to keep the visions as inconspicuous as possible, he decided in the summer of 1851 not to print his wife's testimonies in the widely distributed Review and Herald. In the future her prophetic writings were to be confined to an "Extra," for limited circulation among "those who believe that God can fulfill his word and give visions 'in the last days.'" The "Extras" were scheduled for every two weeks, but only one issue ever appeared. For the next four years Ellen White lived in virtual exile among her own people, being allowed to publish only seven Review and Herald articles, none relating a vision. Most of these brief communications admonished readers to shun worldliness in dress, speech, and action.51

Her visions unappreciated, Ellen White again grew discouraged. The divine revelations came less and less frequently, until she feared her gift was gone. Since her public ministry had depended almost entirely on the visions, she now resigned herself simply to being a Christian wife and mother, a role to which she always attached great significance. James provided little or no encouragement. Over the years he had become increasingly resentful of accusations that he had made his wife's visions a "test" among the Advent Sabbath-keepers and that his Review and Herald promoted her views. Finally, in October, 1855, he exploded. "What has the REVIEW to do with Mrs. W.'s views?" he asked angrily. "The sentiments published in its columns are all drawn from the Holy Scriptures. No writer of the REVIEW has ever referred to them as authority on any point. The REVIEW for five years has not published one of them. Its motto has been, 'The Bible, and the Bible alone, the only rule of faith and duty.'" It was nobody's business, he went on, whether or not he accepted his wife's testimonies.52

The same issue of the Review and Herald containing this outburst also announced that a group of Battle Creek Adventists were taking over publication of the paper, ostensibly because James White's heavy responsibilities had broken his constitution. In recent months he had come to fear that his editorial burdens were threatening his health, and he had publicly expressed a desire to relinquish his position. He especially wanted to free himself from the "whinning complaints" of critics who were writing "poisonous letters" against him. The content of these letters is unknown, but they probably criticized him for his attitude toward the visions. We do know that a short time later he was asked in the Review and Herald to apologize for his low estimate of his wife's gift.53

With Ellen White in the shadows during the early 1850s, the sabbatarian Adventists had not prospered; and her husband's outspokenness made him a likely scapegoat. At a general meeting of sabbatarian leaders in November, 1855, his colleagues replaced him with a twenty-three-year-old convert, Uriah Smith. Then a committee of elders went before the assembly and sorrowfully confessed the church's unfaithfulness in ignoring God's chosen messenger. They made a special point of repudiating James's position on the vision: "To say they are of God, and yet we will not be tested by them, is to say that God's will is not a test or rule for Christians, which is inconsistent and absurd." One of Smith's first acts as the new editor was to reopen the journal's pages to Mrs. White, who happily predicted that God would now smile on the church and "graciously and mercifully revive the gifts." Her humiliation was over; her prophetic role, now secure.54

The Reemergence of Ellen

The lessons of this experience were not lost on Ellen White, who was now emerging as the dominant force among the sabbatarians. In the future the mere threat of divine displeasure helped to sustain her influence. "I saw that God would soon remove all light given through visions unless they were appreciated," she warned the Roosevelt, New York, church in 1861.55 Through the remainder of Ellen's life Adventist leaders coveted her approval and submitted, in public at least, to the authority of her testimonies. Despite her occasional inconsistency and insensitivity, most members clung to the belief that she represented a divine channel of communication. To them, dramatic visions, supernatural healings, and revelations of secret sins were persuasive evidences of a true prophet.

Domestic life for the Whites was scarcely more tranquil than their public life. In April, 1852, the impoverished couple, worn out by years on the road, settled down to a semipermanent home in Rochester, New York, a popular "way station for westward migrants." With the opening of the Erie Canal in the 1820s, thousands of families like the Whites moved into Rochester, stayed for a short time, and then pushed on toward the West. Here, in an old rented house, James and Ellen collected their children about them and set up headquarters for their fledgling church. There were no luxuries. One room housed the press; the others were furnished with pieces of junk Ellen repaired. Food was cheap and simple—turnips instead of potatoes, sauce in place of butter.56

In August, 1854, Ellen's responsibilities increased with the birth of her third child, Willie. After the years of separation she was thankful to be with her children, but their occasional misdeeds caused her so much anxiety her health suffered. For over three years the Whites "toiled on in Rochester through much perplexity and discouragement," receiving little help or sympathy from their erstwhile friends in upstate New York. Their cause was not prospering, but the bills continued to mount. At times James seemed near death, and Ellen feared he might leave her with three children to raise and a debt of two or three thousand dollars. Two visits to Michigan convinced them there were greener pastures to the West; so in the fall of 1855 they shipped press and belongings around Lake Erie to the little town of Battle Creek, thus ending what Ellen called their "captivity." The years of struggle now lay largely in the past; days of fulfillment were just ahead.57

Notes

- J. N. Loughborough, The Great Second Advent Movement: Its Rise and Progress (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1909), p. 306.

- Isaac C. Wellcome, History of the Second Advent Message and Mission, Doctrine and People (Yarmouth, Maine: I. C. Wellcome, 1874), p. 402.

- This story and the account of Ellen's youth which follows are based on two editions of her autobiography: Spiritual Gifts: My Christian Experience, Views and Labors (Battle Creek: James White, 1860); and Life Sketches of Ellen G. White (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1915). Occasional names and dates are taken from C. C. Goen, "Ellen Gould Harmon White," Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, ed. Edward T. James (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), III, 585-88; and "Ellen Gould (Harmon) White," Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, ed. Don F. Neufeld (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1966), pp. 1406-14. Additional details were kindly furnished by the Ellen G. White Estate.

- William Willis, The History of Portland, from 1632 to 1864 (2nd ed.; Portland: Bailey & Noyes, 1865), pp. 68, 728, 769-75; The Portland Directory (Portland: Arthur Shirley, 1834), p. 34.

- The Portland Directory, passim.

- U.S. Public Health Service, A Study of Chronic Mercurialism in the Hatters' Fur-Cutting Industry, Public Health Bulletin No. 234 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1937), p. 39; U.S. Public Health Service, Mercurialism and Its Control in the Felt-Hat Industry, Public Health Bulletin No. 263 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1941), pp. 48-54; Ethel Browning, Toxicity of Industrial Metals (London: Butterworth and Co., 1961), pp. 203-4; May R. Mayers, Occupational Health (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Co., 1969), pp. 79-83; Leonard J. Goldwater, Mercury: A History of Quicksilver (Baltimore: York Press, 1972), pp. 270-75; J. Addison Freeman, "Mercurial Disease among Hatters," Transactions, Medical Society of N.J. (1860), pp. 61-64. Since so many of her contemporaries experienced religious trances similar to Ellen White's, it seems unlikely to me that mercury-induced hallucinations had anything to do with her later visions.

- Sylvester Bliss, Memoirs of William Miller (Boston: Joshua V. Himes, 1853); Francis D. Nichol, The Midnight Cry (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1944), pp. 17-42.

- Bliss, Memoirs, pp. 137-38; Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 43-74.

- Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 75-90, 217. According to David T. Arthur, the Millerites came "from nearly all Protestant groups, most especially Baptist, Congregational, Christian, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches"; "Millerism," in The Rise of Adventism: Religion and Society in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America, ed. Edwin S. Gaustad (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), p. 154.

- Ernest Sandeen, "Millennialism," in The Rise of Adventism, pp. 111, 116; William C. McLoughlin, Jr., Modern Revivalism: Charles Grandison Finney to Billy Graham (New York: Ronald Press, 1959), pp. 105-6.

- John Greenleaf Whittier, "Father Miller," in The Stranger in Lowell (Boston: Waite, Pierce and Co., 1845), pp. 75-83; Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 111-21.

- Religious anxiety, including lying awake most of the night worrying about salvation, was not unusual among New England children Ellen's age; see Joseph F. Kett, "Growing Up in Rural New England, 1800-1840," in Anonymous Americans: Explorations in Nineteenth-Century Social History, ed. Tamara K. Hareven (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971), pp. 1-16.

- Dr. Amariah Brigham, superintendent of the New York Lunatic Asylum in Utica, attributed the insanity of thirty-two patients in three northern asylums to Millerism, which he regarded as a greater threat to the country than yellow fever or cholera; "Millerism," American Journal of Insanity, I (January, 1845), 249-53. The accuracy of Brigham's diagnosis may be questioned, but nineteenth-century American psychiatrists generally believed that excessive religious zeal often precipitated insanity in those already predisposed to mental illness; see Norman Dain, Concepts of Insanity in the United States, 1789-1865 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1964), p. 187. See also Everett N. Dick, "William Miller and the Advent Crisis, 1831-1844" (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1932), pp. 147-51, 194-95; Nichol, Midnight Cry, p. 145; and David L. Rowe, "Thunder and Trumpets: The Millerite Movement and Apocalyptic Thought in Upstate New York, 1800-1845" (Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 1974), pp. 201-5. In his "defense" of the Millerites, Nichol discounts the charges of insanity and suicide (pp. 355-88), while the Seventh-day Adventist historian Dick concludes that "Notwithstanding the numerous false reports it is evident that there was an increase in the number of cases of insanity from religious causes and there were numerous instances of suicides" (p. 194). Rowe's position is similar to Dick's.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 54-56.

- Dick, "William Miller," pp. 211, 233-34, 269; Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 226-27; EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 59-61.

- Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 263-64; James Nix, "The Life and Work of Hiram Edson" (M.A. paper submitted to the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary, Andrews University, 1971), pp. 18-19; David T. Arthur, "Come Out of Babylon: A Study of Millerite Separatism and Denominationalism, 1840-1865" (Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester, 1970), pp. 89, 97-101.

- Nichol, Midnight Cry, pp. 478-81; A. Hale and J. Turner, "Has Not the Savior Come as the Bridegroom?" Advent Mirror, I (January, 1845), 1-4, from a copy in the Adventual Collection, Aurora College.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 64-68; James White (ed.), A Word to the "Little Flock" (Brunswick, Maine: Privately printed, 1847), pp. 14-18. This early tract containing Ellen's first visions is photographically reproduced in Francis D. Nichol, Ellen G. White and Her Critics (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1951), pp. 561-84.

- EGW to Joseph Bates, July 13, 1847 (B-3-1847, White Estate). This important letter was recently discovered in the White Estate vault by Professor Ingemar Lindén. For his views on the shut door, see his Biblicism, Apokalyptik, Utopi: Adventisemens historiska utformning i USA samt dess svenska utveckling till o. 1939 (Uppsala, 1971), pp. 71-84, 449-50; and his unpublished paper in English, "The Significance of the Shut Door Theory in Sabbatarian Adventism, 1845-ca. 1851." Arthur White in "Ellen G. White and the Shut Door Question," recently prepared as an appendix to his forthcoming biography of his grandmother, argues that Ellen White did not mean by the term "shut door" what her contemporaries meant; he ignores the fact that she herself claimed to be in agreement with Joseph Turner. The doctrine of the shut door was particularly popular among Portland Millerites. See Sylvester Bliss to William Miller, February 11, 1845; and J. V. Himes to William Miller, March 12, March 29, and April 22, 1845 (Joshua V. Himes Letters, Massachusetts Historical Society). See also Otis Nichols to William Miller, April 12, 1846 (Miller Papers, Aurora College).

- Godfrey T. Anderson, Outrider of the Apocalypse: Life and Times of Joseph Bates (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1972), p. 63; Loughborough, The Great Second Advent Movement, pp. 257-61; Joseph Bates, The Opening Heavens (New Bedford, Mass.: Benjamin Lindsey, 1846), pp. 6-12.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 95-96; Arthur, "Come Out of Babylon," pp. 138, 144-45.

- Edward Deming Andrews, The People Called Shakers (New ed.; New York: Dover Publications, 1963), pp. 152-53; Herbert A. Wisbey, Jr., Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1964), pp. 160-61; Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet (2nd ed.; New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), pp. 21-22, 55; EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), p. iv.

- Quoted in [James White], "The Gifts of the Gospel Church," R&H, I (April 21, 1851), 69. James White, Ellen's future husband, regarded Himes's statement as the "most heaven-daring and fatal example" of questioning the work of the Holy Spirit that he had ever heard. On Millerite attitudes toward Ellen White, see EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 88-89.

- Bliss, Memories of William Miller, pp. 231-34, 282; David Arnold, "Dream of William Miller," Review and Herald—Extra (n.d.), from a copy in the C. Burton Clark Collection; James White (ed.), Brother Miller's Dream (Oswego, N.Y.: James White, 1850), from a copy in LLU-HR. James White's account of Miller's dream also appeared in Present Truth, I (May, 1850), 73-75.

- Rowe, "Thunder and Trumpets," pp. 266-68.

- J. V. Himes to William Miller, March 12 and March 29, 1845 (Joshua V. Himes Letters, Massachusetts Historical Society). The second woman may have been Sister Durben, who witnessed Ellen's shut-door vision at Exeter in February, 1845.

- "William Foy: A Statement by E. G. White," from an interview with D. E. Robinson, circa 1912 (DF 231, White Estate); William E. Foy, The Christian Experience of William E. Foy, together with the Two Visions He Received in the Months of January and February, 1842 (Portland: J. and C. H. Pearson, 1845), from a reproduction in the White Estate.

- EGW to Mary Harmon Foss, December 22, 1890 (F-37-1890, White Estate); EGW, Life Sketches, p. 77.

- James White, Life Incidents, in Connection with the Great Advent Movement (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1868), pp. 272-73; EGW, Letter 8, 1851 (White Estate).

- For descriptions of Ellen in vision, see Loughborough, Great Second Advent Movement, pp. 204-11; Martha D. Amadon, "Mrs. E. G. White in Vision," November 24, 1925 (DF 105, White Estate); Wellcome, History of the Second Advent Message, pp. 397-402. Although Wellcome remembered catching Ellen twice "to save her from falling upon the floor," she could not recall in later years ever being around Wellcome at the time of a vision; EGW to J. N. Loughborough, August 24, 1874 (Letter 2, 1874, White Estate).

- Amadon, "Mrs. E. G. White in Vision," pp. 1-2.

- Statement of D. T. Bourdeau, February 4, 1891, quoted in Loughborough, Great Second Advent Movement, p. 210. Loughborough (p. 205) noted that Ellen's pulse beat regularly during visions, whereas Merritt Kellogg said her pulse beat very infrequently and almost stopped; M. Kellogg to J. H. Kellogg, June 18, 1906 (Kellogg Collection, MSU). Both men witnessed many visions.

- [Uriah Smith], The Visions of Mrs. E. G. White: A Manifestation of Spiritual Gifts According to the Scriptures (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1868); White, Life Incidents, p. 273; H. E. Carver, Mrs. E. G. White's Claims to Divine Inspiration Examined (2nd ed.; Marion, Iowa: Advent and Sabbath Advocate Press, 1877), pp. 75-76; Dr. W. J. Fairfield to D. M. Canright, December 28, 1887, in Canright, Life of Mrs. E. G. White, Seventh-day Adventist Prophet: Her False Claims Refuted (Cincinnati: Standard Publishing Co., 1919), p. 180; Merritt Kellogg to J. H. Kellogg, June 18, 1906; J. H. Kellogg to R. B. Tower, March 3, 1933 (Ballenger-Mote Papers). Canright (p. 181) also quotes Dr. William Russell of the Western Health Reform Institute as writing on July 12, 1869, "that Mrs. White's visions were the result of a diseased organization or condition of the brain or nervous system." According to Carver, Ellen White in 1865 said that Dr. James Caleb Jackson of Dansville, New York, had "pronounced her a subject of Hysteria." On hysteria, see Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, "The Hysterical Woman: Sex Roles and Role Conflict in 19th-Century America," Social Research, XXXIX (Winter, 1972), 652-78.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts: The Great Controversy, between Christ and His Angels, and Satan and His Angels (Battle Creek: James White, 1858), pp. 27-28; cf. EGW, Life Sketches, p. 30.

- Quoted in Arthur L. White, Ellen G. White: Messenger to the Remnant (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1969), p. 71.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), pp. 292-93; EGW, The Writing and Sending Out of the Testimonies to the Church (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, n.d.), p. 24.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 69-72; EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), p. 30; James and Ellen G. White, Life Sketches: Ancestry, Early Life, Christian Experience, and Extensive Labors, of Elder James White, and His Wife, Mrs. Ellen G. White (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1880), p. 238. The career of a prophetess was in some ways similar to that of a spiritualist medium; and, as R. Laurence Moore has recently pointed out, mediumship was "one of the few career opportunities open to women in the nineteenth century." Moore, "The Spiritualist Medium: A Study of Female Professionalism in Victorian America," American Quarterly, XXVII (May, 1975), 202.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 70-71.

- Ibid., pp. 72-73, 77.

- Robert Darnton, Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1869); Eric T. Carlson, "Charles Poyen Brings Mesmerism to America," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, XV (April, 1960), 121-32; Robert Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966), p. 152. Ellen White regarded mesmerists as "channels for Satan's electric currents"; EGW, "Shall We Consult Spiritualist Physicians?" Testimonies, V, 193.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 88-90.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), pp. 52, 62-63; Edwin Franden Dakin, Mrs. Eddy: The Biography of a Virginal Mind (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1929), pp. 131-32, 159-60.

- "James Springer White," Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, pp. 1419-20.

- Ibid.; White, Life Incidents, pp. 25, 72-75, 96.

- James and Ellen G. White, Life Sketches (1880), p. 238; Ron Graybill, "The Courtship of Ellen Harmon," Insight, January 23, 1973, pp. 4-7. On the warrants for Ellen's arrest, see Otis Nichols to William Miller, April 12, 1846 (Miller Papers). A few years later James White condoned disfellowshipping an Adventist couple for "traveling together to teach the third angel's message"; "Withdrawal of Fellowship," R&H, IV (July 7, 1853), 32.

- EGW, Life Sketches, pp. 105-6.

- Ibid., pp. 110-41; White, Life Incidents, p. 292; James White to Brother and Sister Hastings, August 26, 1848, and October 2, 1848 (White Estate). The Whites possibly abandoned the shut-door doctrine shortly before 1852.

- Arthur, "Come Out of Babylon," p. 142; EGW, Writing and Sending Out of the Testimonies, p. 4; EGW, "The Testimonies Slighted," Testimonies, V, 63-64. For a virtually complete EGW bibliography, see Nichol, Ellen G. White and Her Critics, pp. 691-703.

- EGW, "To Those Who Are Receiving the Seal of the Living God" (broadside dated January 31, 1849, Topsham, Maine), from a copy in LLU-HR; EGW, Early Writings (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1945), pp. 64-67; EGW, MS 4, 1883, quoted in A. L. White, Ellen G. White, p. 32. Bates's prediction of the Second Coming in 1851 is found in his Explanation of the Typical and Anti-Typical Sanctuary (New Bedford, Mass.: Benjamin Lindsey, 1850), p. 10. The meager evidence available suggests that Ellen privately accepted Bates's view but gave it up no later than June, 1851, when she spoke out against setting dates for the return of Christ. See the testimony of her nephew R. E. Belden to W. A. Colcord, October 17, 1929 (Ballenger-Mote Papers); and A. L. White, Ellen G. White, pp. 41-43.

- [James White], "Reply to Bro. Trueldell," R&H, I (April 7, 1851), 64. A complete list of the deleted passages from the early visions is found in Nichol, Ellen G. White and Her Critics, pp. 619-43. James White's admission is reported in H. E. Carver, Mrs. E. G. White's Claims to Divine Inspiration Examined (2nd ed.; Marion, Iowa: Advent and Sabbath Advocate Press, 1877), pp. 10-11. A different view of the White-Carver conversation is given in J. N. Loughborough, "Response," R&H, XXVIII (September 25, 1866), 133-34.

- EGW to Brother and Sister Dodge, July 21, 1851 (D-4-1851, White Estate); EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), p. 294; Second Advent Review and Sabbath Herald... Extra, II (July 21, 1851), 4. For a typical statement by James White on the independence of his theology from the visions, see "Palsshaw, Mich.," R&H, XXIV (August 23, 1864), 100. Mrs. White's seven articles appeared in the following issues of the R&H: III (June 10, 1852), 21; III (February 17, 1853), 155-56; III (April 14, 1853), 192; IV (August 11, 1853), 53; V (July 25, 1854), 197; VI (September 19, 1854), 45-46; VI (June 12, 1855), 246. Her April 14, 1853, note, in which she compares herself with the writers of the Bible, corrects an error regarding one of her visions.

- EGW, "Communication from Sister White," R&H, VII (January 10, 1856), 118; J[ames] W[hite], "A Test," R&H, VII (October 16, 1855), 61-62.

- "To the Church of God," R&H, VII (October 16, 1855), 60; J[ames] W[hite], "The Cause," R&H, VII (August 7, 1855), 20; Hiram Bingham to James White, R&H, VII (February 14, 1856), 158.

- "Business Proceedings of the Conference at Battle Creek, Mich.," R&H, VII (December 4, 1855), 76; Joseph Bates, J. H. Waggoner, and M. E. Cornell, "Address," ibid., 78-79; EGW, "Communication from Sister White," p. 118.

- EGW to the Church in Roosevelt and Vicinity, August 3, 1861 (R-16a-1861, White Estate).

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), pp. 160-61; Blake McKelvey, Rochester: The Water-Power City, 1821-1854 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1945), pp. 163, 334.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1860), pp. 165, 192-203; James and Ellen White, Life Sketches (1880), pp. 323-24; EGW, Life Sketches, p. 157; Defense of Eld. James White and Wife: Vindication of Their Moral and Christian Character (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1870), p. 4.