Prophetess of of Health

Chapter 4: The Dansville Days

By Ronald L. Numbers

"..it is as truly a sin against Heaven, to violate a law of life, as to break one of the ten commandments."

L. B. Coles1

"It is as truly a sin to violate the laws of our being as it is to break the ten commandments."

Ellen G. White2

Ellen White's chance reading of Jackson's article on diphtheria in January, 1863, was by no means the first Adventist encounter with health reform. Adventist involvement actually went back to the days before the Great Disappointment of 1844 when prominent Millerites such as the Reverend Charles Fitch, Ezekiel Hale, Jr., and Dr. Larkin B. Coles publicly allied themselves with the reformers. Such an alliance was not at all unusual; as Charles E. Rosenberg has pointed out, the unorthodox in religion commonly displayed a marked affinity for heterodox medicine, which they tended to view in a moral rather than in a scientific light.3

In the early 1860s Jackson's water cure in Dansville became a favorite retreat for ailing Sunday-keeping Adventists. Daniel T. Taylor, Adventist hymnist and minister, resided at Our Home for an entire year while undergoing the water treatment — "mostly hot or warm externally & internally perpetually." He in turn influenced Joshua V. Himes, formerly Miller's top assistant, to join him when the latter's health broke early in 1861. Elder and Mrs. Himes had been friends of the Jacksons for some time, but it was Joshua's remarkable cure at Our Home that finally made wholehearted health reformers out of them. Favorable notices of Jackson's books and water cure began appearing in Himes's Voice of the Prophets, and later, after Himes moved to Michigan and changed the name of his paper to Voice of the West, each issue for a while featured a "Health Department," to which Jackson was an occasional contributor.4

Even the sabbatarians displayed more than passing interest in the health-reform movement. Joseph Bates, as we have already noted, adopted Grahamism in 1843 and spent decades as a temperance crusader. John Loughborough took to eating Graham bread and reading the Water-Cure Journal in 1848, after learning about health reform from an uncle in western New York. J. P. Kellogg, of Tyrone, Michigan — father of Merritt, John Harvey, Will Keith, and thirteen other children — raised his sizable brood by the Water-Cure Journal and sent three of his older sons, including Merritt, to reform-minded Oberlin College. Roswell F. Cottrell, who served on the editorial committee of the Review and Herald after the move to Battle Creek, began experimenting in the late 1840s with a vegetarian diet and a daily bath.5 All these men were closely associated with the Whites and undoubtedly spoke to them of their experiences in health reform.

And there were others. J. W. Clarke, of Green Lake County, Wisconsin, turned to vegetarianism and hydropathy in the late 1840s. William McAndrew in Michigan and an anonymous sister in Rhode Island embraced health reform in the early 1850s. Uriah Smith's sister Annie, after copy-editing the Review and Herald in Saratoga Springs and Rochester, spent several months at a water cure before her death in 1855. H. F. Phelps and H. C. Miller were reading water-cure publications and taking their first steps toward health reform in the early 1860s. And by early 1863 Marietta V. Cook, of Kirkville, New York, was dressing in the American costume, enjoying meals of "plain food," and corresponding with the doctors at Dansville.6

Whites Discover Dr. Jackson

Despite these early signs of interest, Seventh-day Adventists as a body did not awaken to the cause of health reform until 1863, a period during which a major change in attitudes toward health occurred among the leaders of the sect. One of the first indications of a health-reform awakening was the reprinting of Dr. Jackson's "Diphtheria, Its Causes, Treatment and Cure" on the front page of the February 17 issue of the Review and Herald, accompanied by a note from the pen of James White recommending the hydropathic approach to medicine. On the basis of Ellen's recent experience using Jackson's treatments on her two boys, as well as on the six-year-old child of Elder Moses Hull, James had come to place "a good degree of confidence in [Jackson's] manner of treating diseases." He failed to mention that over two years earlier, while suffering from lung fever in Wisconsin, he had had another successful encounter with the water cure.7

The Jackson article not only described specific treatments for diphtheria, it spelled out the basic principles of health reform in tips on eating properly, dressing sensibly, and breathing lots of fresh air. We know that James White was beginning to recognize the importance of these measures, for in the February 10 Review and Herald he called air, water, and light "God's great remedies," preferable to "doctors and their drugs." He reported proudly that both he and his wife slept year-round with the windows wide open and took "a cold-water sponge-bath" every morning. Four pages later he inserted an article on the evils of sleeping in poorly ventilated rooms, taken from an exchange publication. The language appears to be Dr. W. W. Hall's, but the selection is not found in earlier issues of Hall's Journal of Health.8

During the month of May, James White continued to focus on hygienic living in the Review and Herald with a note from Dio Lewis on dress reform and two extracts from Hall's Journal of Health, one urging a meatless, low-fat diet during spring and summer, the other recommending two meals a day.9 Thus by June of 1863 Seventh-day Adventists were already in possession of the main outlines of the health reform message. What they now needed to become a church of health reformers was not additional information, but a sign from God indicating his pleasure.10

Health Reform "Vision"

Divine approval of the health crusade came on the evening of June 5, 1863, while Ellen White and a dozen friends were kneeling in prayer at the home of the Aaron Hilliards, just outside the village of Otsego, Michigan. Earlier that Friday the Whites had driven up from Battle Creek with several carriages full of Adventists to lend their support to a series of tent meetings being held in the village. At sundown the Battle Creek visitors gathered in the Hilliard home to usher in the Sabbath with prayer. Ellen, the first to speak, began by asking the Lord for strength and encouragement. Lately, neither she nor James had been well. Her familiar fainting spells were recurring once or twice a day, while excessive cares and responsibilities had brought James to the verge of a mental and physical collapse.11

As Ellen prayed, she slipped to her husband's side and rested her hands on his bowed shoulders. In a short time she was off in vision, receiving heaven-sent instructions on the preservation and restoration of health. She and James were directed not to assume such a heavy burden in the Adventist cause, but to share their responsibilities with others. She was to curtail her sewing and entertaining; James was to quit dwelling on "the dark, gloomy side" of life. In a less personal vein, she saw that it was a religious duty for God's people to care for their health and not violate the laws of life. The Lord wanted them "to come out against intemperance of every kind, intemperance in working, in eating, in drinking, and in drugging." They were to be his instruments in directing the world "to God's great medicine, water, pure soft water, for diseases, for health, for cleanliness, and for luxury."12

For a couple of weeks following her vision Ellen White seemed reluctant to say much about its contents. Then one day while riding in a carriage with Horatio S. Lay, a self-styled Adventist physician from Allegan, she briefly mentioned some of the things she had seen. What he heard whetted his curiosity. When the Whites visited Allegan for a funeral a few days later, he took the opportunity to invite them and nine-year-old Willie home to dinner. After the meal he immediately began pumping Mrs. White for more details of her recent vision. As Willie recalled seventy-three years later, his mother at first demurred, saying "that she was not familiar with medical language, and that much of the matter presented to her was so different from the commonly accepted views that she feared she could not relate it so that it could be understood." Lay's persistence eventually overcame her hesitance, however, and for two hours she related what she had witnessed. According to Willie,

She said that pain and sickness were not ordinarily, as was commonly supposed, due to a foreign influence, attacking the body, but that they were in most cases an effort of nature to overcome unnatural conditions resulting from the transgression of some of nature's laws. She said that by the use of poisonous drugs many bring upon themselves lifelong illness, and that it had been revealed to her that more deaths had resulted from drug taking than from any other cause.

At this point Lay interrupted to say that certain "wise and eminent physicians" were currently teaching exactly what she had been shown. Thus encouraged, she went on to condemn the use of all stimulants and narcotics, to caution against meat eating and to emphasize "the remedial value of water treatments, pure air, and sunshine."13

Ellen White's first published account of her June 5 vision, a short thirty-two-page sketch tucked into the fourth volume of Spiritual Gifts did not appear until fifteen months after the event. She had hoped to provide a fuller report, but other duties and poor health had made that impossible. For the past year she had labored at her desk almost constantly, often writing twelve hours a day. At times her head continually ached, and for weeks she seldom got more than two hours' sleep at night.14

In her essay "Health," which reads in places like L. B. Coles, she recited the established principles of health reform, attributing them to her recent vision. Willful violations of the laws of health — particularly "Intemperance in eating and drinking, and the indulgence of base passions" — caused the greatest human degeneracy. Tobacco, tea, and coffee depraved the appetite, prostrated the system, and blunted the spiritual sensibilities. Meat-eating led to untold diseases; swine's flesh alone produced "scrofula, leprosy and cancerous humors." Living in low-lying areas exposed one to fever-producing "poisonous miasma."15

Her strongest language, however, was reserved for the medical profession: "I was shown that more deaths have been caused by drug-taking than from all other causes combined. If there was in the land one physician in the place of thousands, a vast amount of premature mortality would be prevented." All drugs, vegetable as well as mineral, were proscribed. The Lord specifically and graphically forbade the use of opium, mercury, calomel, quinine, and strychnine. "A branch was presented before me bearing flat seeds," Ellen recalled. "Upon it was written, Nux vomica, strychnine. Beneath was written, No antidote." Of all the medical sects, only drugless hydropathy received divine sanction. Since medicines were so dangerous and had "no power to cure," the only safe course was to rely on the natural remedies recommended by the health reformers: pure soft water, sunshine, fresh air, and simple food — preferably eaten only twice a day.16

Self-Appointed Health Reformer

In the months following her June 5 vision, as Ellen White traveled about the Midwest and Northeast speaking on her favorite topic of health, curious listeners sometimes inquired if she had not previously read the Laws of Life, the Water-Cure Journal, or any of the works of Drs. Jackson and Trall. Her stock reply was that she had not and would not until she had fully written out her views, "lest it should be said that I had received my light upon the subject of health from physicians, and not from the Lord." But the embarrassing questions persisted until finally she issued a formal statement in the Review and Herald disclaiming any familiarity with health-reform publications prior to receiving and writing out her vision. Referring specifically to Jackson's, she said: "I did not know that such works existed until September, 1863, when in Boston, Mass., my husband saw them advertised in a periodical called the Voice of the Prophets, published by Eld. J. V. Himes. My husband ordered the works from Dansville and received them at Topsham, Maine. His business gave him no time to peruse them, and as I determined not to read them until I had written out my views, the books remained in their wrappers."17

In her anxiety to appear uninfluenced by any earthly agency — "My views were written independent of books or of the opinion of others" — Ellen White failed to mention certain pertinent facts. Not only did she ignore her reading of Jackson's article on diphtheria nearly six months before her vision, but she incorrectly gave the time when James had first learned of Jackson's other works. On August 13, 1863, one month before James supposedly had any knowledge of Dansville, Dr. Jackson wrote him apologizing for his long delay in replying to White's request for information about his books. It seems that James had written Jackson sometime in June, for in December of 1864 he stated that eighteen months earlier (June, 1863) he had sent off to Dansville "for an assortment of their works, that might cost from ten to twenty-five dollars. Then we knew not the name of a single publication offered for sale at that house. We heard from reliable sources that there was something valuable there, and resolved to put in for a share."18

If James's account is accurate, then Ellen was also wrong in implying that her husband first learned of the Dansville publications from an advertisement in the Voice of the Prophets. James said that he knew not "the name of a single publication" when he wrote Dr. Jackson; but had he read the notice in Himes's journal, he would have known at least three titles: Consumption and The Sexual Organism by Jackson, and Pathology of the Reproductive Organs by Trall.19

Two other details bear on the accuracy of Ellen White's disclaimer. She insisted that the books from Dansville remained in their wrappers after arriving in Topsham, but already by December 12 James was mailing Jackson's Consumption from Topsham to a friend in Brookfield, New York. And if Ellen White regularly read the Review and Herald that her husband edited, as surely she did, then she saw in the October 27 issue an article by Dr. Jackson on hoops, taken from the Laws of Life.20

Ellen White's conversion to health reform did much to change the eating habits of Seventh-day Adventists. The revolution began in her own household. She desperately wanted to switch all at once to the two-meal Graham system, but her stomach rebelled. Having been a self-confessed "great meat-eater," she found the substitution of unbolted wheat bread intolerable. For a few meals she could eat nothing, but at last the victory was gained when she resolutely placed her hands on her recalcitrant stomach and warned it, "You may wait until you can eat bread." Before long she actually came to enjoy the once-hated article and accorded it a central place, along with fruit and vegetables, in the White family diet. "Our plain food, eaten twice a day, is enjoyed with a keen relish," she was able to write by 1864. "We have no meat, cake, or any rich food upon our table. We use no lard, but in its place, milk, cream, and some butter. We have our food prepared with but little salt, and have dispensed with spices of all kinds. We breakfast at seven, and take our dinner at one." On this regimen, her health took a marked turn for the better. Her periodic "shocks of paralysis" ceased; her "dropsy and heart disease" abated; and her weight dropped by twenty-five unneeded pounds she had gained since her youth. For years she had never felt better.21

Unfortunately, not all the members of her family shared her experience. Her husband's health improved at first but then declined alarmingly in the next couple years, and during the winter of 1863-64 two of her boys came down with critical cases of pneumonia. Despite (or because of) the efforts of a physician, her eldest son, Henry, died of the disease at age sixteen and was laid to rest beside his baby brother, Herbert, in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Battle Creek. A short time after the funeral Willie, too, caught "lung fever." This time his frightened parents decided not to consult a physician, but to administer water treatments and pray for his recovery. For five anxious days he lingered near death, but then his mother had an inspired dream in which a heavenly physician assured her that Willie would not die, "for he has not the injurious influence of drugs to recover from." All he needed was cool, fresh air, said the messenger; "Stove heat destroys the vitality of the air, and weakens the lungs." By the next day Willie was feeling better and was soon fully recovered. Needless to say, these two events substantially increased Ellen White's faith in the curative power of water over that of earthly physicians.22

For most Adventists, acceptance of health reform meant principally three things: a vegetarian diet, two meals a day, and no drugs or stimulants. Its progress among them was immortalized in a song, "The Health Reform," composed by Elder Roswell Cottrell:

When men are beginning the work of reform,

Casting off their gross idols, as ships in a storm

Cast off the most cumbersome part of their freight,

They feel the improvement and progress is great.Oh, yes, I see it is so,

And the clearer it is the farther I go.First goes the tobacco, most filthy of all,

Then drugs, pork and whisky, together must fall,

Then coffee and spices, and sweet-meats and tea,

And fine flour and flesh-meats and pickles must flee.Oh, yes, I see it is so,

And the clearer it is the farther I go.Things hurtful and poisonous laying aside,

The good and the wholesome alone must abide;

And these with a moderate, temperate use,

At regular seasons, avoiding abuse.Oh, yes, I see it is so,

And the clearer it is the farther I go.A proper proportion of labor and rest,

With good air and water, the purest and best,

And clothing constructed to be a defense,

Not following custom, but good common sense.Oh, yes, I see it is so,

And the clearer it is the farther I go.Our frames disencumbered, our spirits are free,

Our minds once beclouded now clearly can see;

Brute passions no longer our natures control,

But instead we act worthy a rational soul.Oh, yes, I see it is so,

And the clearer it is the farther I go.Faith, patience and meekness, more brightly now shine

Evincing the human allied to divine;

And religion, once viewed as a shield against wrath,

Becomes a delightsome and glorious path.Oh, yes, they know it is so,

Who have chosen this light-giving pathway to go.23

Dansville

Since so few knew anything about preparing meatless meals or giving fomentations, the Review and Herald undertook the task of educating the uninitiated by regularly excerpting appropriate selections from the writings of prominent reformers like Russell Trall, Dio Lewis, and L. B. Coles. Individuals who desired additional help could send in to the Review office in Battle Creek for cookbooks by Trall and Jackson or for special irons to make "Graham gems," a popular form of whole-wheat bread. A handful of Adventists were able to draw upon their own experiences to assist their fellow members through the transition. Martha Byington Amadon, daughter of the General Conference president, thoughtfully provided readers of the Review and Herald with hints on "How to Use Graham Flour," a ubiquitous substance used in making everything from bread and biscuits to puddings and cakes. By the time of the 1864 Michigan State Fair some Battle Creek sisters were so proficient at vegetarian cookery that they hauled stoves to the fairgrounds and publicly demonstrated their newly acquired skills.24

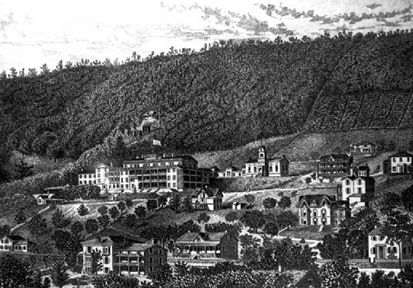

Right from the beginning of their health-reform days the Seventh-day Adventists, like their Sunday-keeping brethren, displayed a singular fondness for the Jackson water cure in Dansville. The person apparently most responsible for establishing this relationship was John N. Andrews, an itinerant preacher — later General Conference president and pioneer missionary — who in the early sixties was pitching his evangelistic tent in the towns and villages of western New York. It is not clear how or when he first learned of Our Home, but he possibly heard of it through Daniel T. Taylor, whom he had come to know while writing his History of the Sabbath, and whose brother Charles was a colleague of his in the ministry. The unpublished diary of Mrs. Andrews reveals that she and her husband were routinely using water treatments in their home by the spring of 1863 and that in January, 1864, John's co-laborers offered to send him to Our Home for a few weeks of rest and treatment. John, "loath to quit" his preaching, declined the invitation, but a few months later sent his badly crippled six-year-old son Mellie (Charles Melville) for a fifteen-week stay. After several weeks Mrs. Andrews joined her boy at Dansville, and although she at first felt "like a stranger in a strange land" amid so many dress reformers, she eventually came to respect the place and its dedicated physicians. Mellie's leg improved remarkably at the water cure, and by July he was able to return home nearly normal. Meanwhile, both his parents had become zealous health reformers, and as his father preached throughout the state, he also solicited subscriptions for the Laws of Life in order to earn a free copy of Trall's Hydropathic Encyclopedia.25

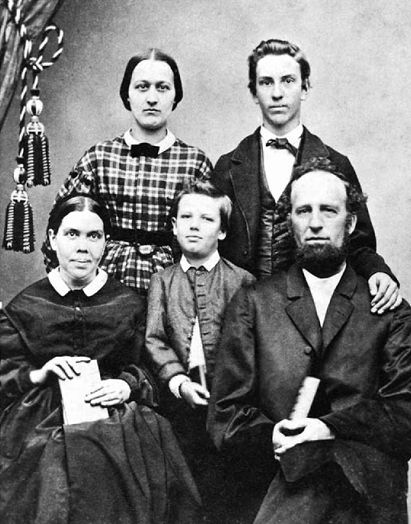

Possibly encouraged by the Andrewses, James and Ellen White decided in late autumn, 1864, that the time was right for a firsthand look at the Dansville facilities. They had contemplated such a visit since shortly after Ellen's June 5 vision, when James had written Jackson inquiring about a ministerial discount; but the trip had been postponed until Ellen had sketched out most of her vision, to avoid insinuations that she had come under the influence of the Dansville reformers. At last on Monday, September 5, following a weekend stopover in Rochester with the Andrewses, the Whites arrived at Our Home. Within a few days they were joined by Edson and Willie and their chaperone, Adelia Patten. Although the local press ignored the presence of the prophetess and her family, Dr. Jackson welcomed them all warmly and even invited Mrs. White to address a health-reform convention then in progress. Unlike Mrs. Andrews only a few months earlier, she had little reason to feel like a stranger, for already a colony of Adventists was forming at the water cure. Besides her family and Miss Patten, at least seven other Sabbath-keepers were there, including Dr. and Mrs. Horatio Lay, John Andrews, and Hiram Edson.26

For three weeks the Whites remained as guests of Our Home, gleaning all the information they could from daily observations of hydrotherapy and from Jackson's frequent lectures. Adelia Patten described the doctor's style: "he combines his theology, his medical instructions, his comical nonsense and his theatrical gestures all into his discourses. He flies about like a young man, and will come into the lecture hall with an old blue woolen cap on[,] which he takes off and puts under his arm and walks along and mounts the rostrum with all the firmness of an experienced lecturer."27

Fascinating to Ellen White was the "science" of phrenology, which Dr. Jackson practiced at five dollars a reading. Soon after the arrival of Edson and Willie she took them to the doctor for evaluations of their "constitutional organization, functional activity, temperament, predisposition to disease, natural aptitudes for business, fitness for connubial and maternal conditions, etc., etc." Writing to friends, she could scarcely conceal her elation with Jackson's flattering analysis: "I think Dr. Jackson gave an accurate account of the disposition and organization of our children. He pronounced Willie's head to be one of the best that has ever come under his observation. He gave a good description of Edson's character and peculiarities. I think this examination will be worth everything to Edson." Presumably she was not so pleased with the doctor's diagnosis of her condition as hysteria.28

The American costume of "short" skirts over pants, worn by Dr. Harriet Austin and the other women of Our Home, also caught Ellen's fancy. The outfits did strike her as being on the mannish side, but she thought slight modifications could easily remedy that. "They have all styles of dress here," she wrote from Dansville.

Some are very becoming, if not so short. We shall get patterns from this place, and I think we can get out a style of dress more healthful than we now wear, and yet not be bloomer or the American costume. Our dresses according to my idea, should be from four to six inches shorter than now worn, and should in no case reach lower than the top of the heel of the shoe, and could be a little shorter even than this with all modesty. I am going to get up a style of dress on my own hook which will accord perfectly with that which has been shown me [in vision]. Health demands it. Our feeble women must dispense with heavy skirts and tight waists if they value health.

"[D]on't groan now," she told her correspondent. "I am not going to extremes, but conscience and health requires a reform."29

The Battle Creek visitors found the food at Our Home plain even for their tastes. "We have the crackers," wrote Miss Patten; "they don't furnish 'gems' only in case of a wedding or some other extra occasion. They don't have salt. The pudding is thin and fresh squash and cabbage without salt or vinegar and oh such times. I had a little salt dish this noon and wanted to pocket the salt that was left and as none of our company had an envelope so had Bro. W[hite] tip it into his pass book."30

Even with an offended palate, Ellen White was so impressed with the overall program at Dansville that she began toying with the idea of setting up a similar institution in Battle Creek, "to which our Sabbath keeping invalids can resort." At their own water cure the strait-laced Adventists could avoid certain problems encountered at Our Home. Dr. Jackson, she reported regretfully, allowed his patients to "have pleasureable excitement to keep their spirits up. They play cards for amusement, have a dance once a week and seem to mix these things up with religion." While such activities might be appropriate for those who had "no hope for a better life," they surely could not be condoned by Christians looking for Christ's return.31

Following three profitable weeks at Dansville, the Whites headed home to Battle Creek, brimming with enthusiasm for sitz baths, short skirts, and Graham mush. On the return trip they once again stopped for a brief visit with the Andrewses and indulged themselves in a little fresh fish, which James thoughtfully went out and purchased for breakfast one morning. Visions or not, vegetarianism was going to be a battle! For the next eleven months, while Sherman marched through Georgia and Grant pursued Lee in Virginia, James and Ellen campaigned throughout the Northern states proclaiming the gospel of health and salvation — at times, complained some dissident members, to the exclusion of other more pressing issues. It was difficult for these critics to understand why "nothing was shown about the duty of the brethren in view of the draft, but a vision was given showing the length at which women should wear their dresses."32

How to Live

During these years before the Adventists had their own water cure, Ellen White could often be seen in Battle Creek going from house to house giving hydropathic treatments. In addition to this and her frequent speaking engagements, she found time to assemble six pamphlets on health reform, which were then bound together into a little volume called Health; or, How to Live, the subtitle being borrowed from a work recently issued by the house of Fowler and Wells. Each pamphlet focused on a single aspect of healthful living — diet, hydropathy, drugs, fresh air and sunlight, clothing, and exercise — and included material written both by Mrs. White and by other reformers. Most of the major names were there: Graham, Trall, Dio Lewis, Jackson, Coles, Mann, and many more. Although their selections were carefully chosen to avoid the inclusion of objectionable passages, like Coles's recommendation of bowling as an excellent form of exercise, crude phrenological analyses and sweeping statements about prenatal influences remained untouched. Ellen White's contribution, a six-part essay on "Disease and Its Causes," dealt with "Health, happiness and [the] miseries of domestic life, and the bearing which these have upon the prospects of obtaining the life to come." And to give an indication of the state of health reform among Adventists, James White told of his recent visit to Dansville.33

To round out the volume, twelve of Battle Creek's finest reformed cooks assembled a special collection of recipes for pies, puddings, fruits, and vegetables. Among their favorites were:

Gems. — Into cold water stir Graham flour sufficient to make a batter about the same consistency as that used for ordinary griddle cakes. Bake in a hot oven, in the cast-iron bread pans. The pans should be heated before putting in the batter.

Note. — This makes delicious bread.... If hard water is used, they are apt to be slightly tough. A small quantity of sweet milk will remedy this defect.

Graham Pudding. — This is made by stirring flour into boiling water, as in making hasty pudding. It can be made in twenty minutes, but is improved by boiling slowly an hour. Care is needed that it does not burn. It can be eaten when warm or cold, with milk, sugar, or sauce, as best suits the eater.

When left to cool, it should be dipped into cups or dishes to mold, as this improves the appearance of the table as well as the dish itself. Before molding, stoned dates, or nice apples thinly sliced, or fresh berries, may be added, stirring as they are dropped in. This adds to the flavor, and with many does away with the necessity for salt or some rich sauce to make it eatable....

When cold, cut in slices, dip in flour, and fry as griddle-cakes. It makes a most healthful head-cheese.

In the opinion of the experts, this dish, next to Graham bread, was the most popular staple on health reform tables.34

According to Ellen White, the selections accompanying her essays in How to Live were included not to indicate her sources but solely to show the harmony of her views with what she regarded as the most enlightened medical opinion of her day. "[A]fter I had written my six articles for How to Live," she stated, "I then searched the various works on Hygiene and was surprised to find them so nearly in harmony with what the Lord had revealed to me. And to show this harmony... I determined to publish How to Live, in which I largely extracted from the works referred to." Even the casual reader must agree that a striking similarity does exist between Mrs. White's ideas and those commonly expressed by the health reformers. But the similarity may not be as coincidental as she implies. If we accept the testimony of John Harvey Kellogg, who as a teenager set type for How to Live, Ellen White was more than passingly familiar with at least Coles's Philosophy of Health by the time she wrote her articles. It seems that she shared with Sylvester Graham (and others) a reluctance to acknowledge her intellectual and literary debts.35

Although the church leaders probably never realized their goal of placing How to Live in every Adventist home, Mrs. White's little digest of health-reform literature sold well at $1.25 a bound copy and generally elicited a positive response. The only serious problem it encountered was the tendency of some readers to ascribe to the prophetess every notion contained in its pages. This created awkward situations at times and once moved her to protest that she did not endorse Coles's opinion, expressed in How to Live, that babies should be nursed only three times a day. With her blessing upon them, the various works of the health reformers began circulating freely among Adventists, and the Publishing Office in Battle Creek was soon reporting the sale of large quantities of books by Trall, Jackson, Graham, and Mann — and "tons" of pans for baking Graham bread.36

Return to Dansville

Despite the ground swell of reform, many Adventists continued to suffer from poor health. Physically speaking, church leadership reached its nadir in the summer of 1865 when a wave of sickness prostrated many of the leaders and brought activities at headquarters to a virtual standstill. James White and John Loughborough were both forced to their beds, causing the three-man General Conference committee to suspend meetings indefinitely. At the same time sickness prevented the Michigan state conference committee from carrying on its business and compelled Uriah Smith temporarily to relinquish his duties as editor of the Review and Herald.37

James White was the most critically ill of all. During the past year he had exhausted himself helping his wife prepare the pamphlets on How to Live, assisting Adventist boys drafted into the Union army, making arrangements for a general conference session in May, and attempting to put out the fires of rebellion in Iowa, where dissidents were splintering off to form a rival sect, the Church of God (Adventist). The strain of these additional duties severely taxed his already weakened system and literally drove him to the brink of death. Early in the morning of August 16, while he and Ellen were out walking in a neighbor's garden, a sudden "stroke of paralysis" passed through the right side of his body, leaving him practically helpless. Somehow his wife managed to get him into the house where she heard him mutter, "Pray, pray." Her prayers seemed to help a little, but still his right arm remained partially paralyzed, his nervous system shattered, and his brain "somewhat disturbed." Shock treatments with a galvanic battery were tried for a while; but this seemed like such a denial of faith in God's healing power, Ellen resolved to rely solely on the simple hydropathic techniques she had recently learned. For nearly five weeks she tenderly nursed James at home until she was too weak to continue the effort herself and could find no one else in Battle Creek willing to assume the responsibility for her husband's life. After much prayer she finally decided to take him back to Dansville and place him under the care of the skilled physicians at Our Home.38

Sympathetic friends and relatives waved sadly from the platform as the "Seventh-day invalid party" pulled slowly out of Battle Creek station on the morning of September 14. Accompanying the Whites on the trip to New York were Loughborough, Smith, Sister M. F. Maxson, and Dr. Horatio Lay, who had come from Dansville to escort the ailing Adventists to Our Home. After an arduous weeklong journey that included a stopover in Rochester the pathetic little band, apparently no worse for the wear, arrived at their destination, where Dr. Jackson warmly greeted them. The day after arrival the doctor examined his new patients and issued the long-awaited prognoses, which Uriah Smith reported in the Review and Herald. James White, clearly the most critical case, would have to remain at the water cure for six to eight months, during which time Ellen White would also take treatments. Loughborough might recover in five or six months. "But the Editor of the Review, unfortunately for its readers, is to be let off in five or six weeks."39

The Whites soon settled into the Dansville routine. Small rooms were found close by the institution where Ellen could set up housekeeping and nursing operations. Daily she made the beds and tidied the rooms, not only for her husband and herself, but also for the other Battle Creek ministers who occupied an adjoining room. She insisted on spending as little time indoors as possible. When not taking water treatments, she and James strolled about the grounds basking in the sunlight and fresh autumn air. Three times each day they met with their brethren — including Elder D. T. Bourdeau from Vermont — for special seasons of prayer in James's behalf. Nights were the worst. Constant pain made sleep almost impossible for James, and Ellen sacrificed hours of her own much-needed rest rubbing his shoulders and arms to provide temporary relief. Often prayer proved to be the only effective therapy in bringing sleep to the weary preacher.40

Understandably, the Whites were somewhat embarrassed by their present state of health, especially in view of their outspoken praise of health reform over the past couple of years. Certainly their own lives were not very effective witnesses to the power of abstemious living. Ellen feared that her husband's "professed friends" would secretly rejoice in his affliction and chalk it up to sin in his life. To assist in meeting possible criticism, she wrote home to her children in Battle Creek asking them to send "the health journal in which [Sylvester] Graham gives his apology for being sick." As far as the Whites were concerned, James's illness had not resulted from personal sin but from prolonged and unceasing labor for the Lord.41

Early in October James's colleagues on the General Conference committee called on Seventh-day Adventists everywhere to set aside Sabbath, the fourteenth, as a day of fasting and prayer for their stricken leader. At Dansville the Whites retreated a short distance from Our Home to a beautiful grove, where they spent the afternoon united in prayer with Elders Loughborough, Bourdeau, and Smith. The experience filled James with renewed hope, and the following day he appeared to be on the road to recovery. By mid-November, however, he had again slipped to a critical condition, and friends despaired for his very life. When he grew so weak he could no longer walk the short distance up the hill to the dining hall, John Loughborough kindly volunteered to bring baskets of food to the Whites' room.42

By this time Ellen was beginning to show signs of strain and left Dansville for a few days to be with her two boys, who had recently arrived in Rochester from Michigan. But even away from the water cure she could not get her mind off her suffering husband or the physicians caring for him. Her first night in Rochester she dreamed of being back at Dansville "exalting God and our Saviour as the great Physician and the Deliverer of His afflicted, suffering children." Apparently friction was already developing between her and the staff of Our Home, for in this dream, she told James, "Dr. Jackson was near me, afraid that his patients would hear me, and wished to lay his hand upon me and hinder me, but he was awed and dared not move; he seemed held by the power of God. I awoke very happy." In a less dramatic tone she also reported that her diet was about the same as at Dansville — "Mornings I eat mush, gems, and uncooked apples. At dinner baked potatoes, raw apples, and gems" — and that she was confident James would "astonish the whole [medical] fraternity by a speedy recovery to health."43

Mrs. White remained in Rochester only briefly before returning to her husband's side. On her thirty-eighth birthday, November 26, she celebrated with a dinner of "Graham mush, hard Graham crackers, applesauce, sugar, and a cup of milk." The next day she and James met with Loughborough for an emotional season of prayer. "For more than one hour we could only rejoice and triumph in God," she later wrote. "We shouted the high praise of God." This "heavenly refreshing" had a cheering effect on James, but only temporarily.44

James' Ill Health Continues

Shortly after this experience Ellen White became impressed with the advantages of removing James to Battle Creek, where he could recover in the more congenial atmosphere of his own home. Besides, several aspects of Dansville life were causing her deep concern. First, the inactivity prescribed for James was obviously not working. What he needed, she thought, was "exercise and moderate, useful labor." Second, James's mind was being "confused" by the religious teachings of Dr. Jackson, which did not conform with what Ellen had "received from higher and unerring authority." Third, the amusements encouraged by the management, especially dancing and card-playing, seemed out of harmony with true Christianity. Although Jackson always exempted his Adventist patients from such activities, Ellen still felt uneasy around such blatant manifestations of worldliness. One day when she was mistakenly approached in the bathroom for a donation to pay the fiddler at the dances, she declared to the doubtless startled solicitor that as a "follower of Jesus" she could not contribute and then proceeded to give an impromptu lecture on Christian principles to the ladies in the room.45

By early December Ellen's own strength was rapidly slipping away; and when James suffered through a particularly bad night on the fourth, she abruptly decided the time had come to leave. The doctors were notified, trunks were packed, and early the next morning in driving sleet she departed for Rochester with a bundled-up James. For three weeks the Whites stayed in that city, enjoying the hospitality of Adventist friends. At James's request, other believers were summoned from surrounding churches to come to Rochester and join with the family in prayer for his recovery.46

While praying on Christmas evening, Ellen White was "wrapped in a vision of God's glory." To her immense relief, she saw that her husband would eventually recover. She also received a message of lasting importance: Seventh-day Adventists should open their own home for the sick, so that they would no longer have "to go to popular water-cure institutions for the recovery of health, where there is not sympathy for our faith." Adventists were to "have an institution of their own, under their own control, for the benefit of the diseased and suffering among us, who wish to have health and strength that they may glorify God in their bodies and spirits which are his." Although she appreciated "the kind attention and respect" she had received from the staff at Our Home, she wanted no more sad treks to Dansville, where "the sophistry of the devil" prevailed.47

New Year's Day the Whites boarded the train in Rochester and departed for home and friends in Michigan. Aided by his wife and sustained by Graham mush and gems, James survived the difficult trip to Battle Creek and arrived in good spirits. He was now fifty pounds below his normal weight, but fresh air, moderate exercise, and Ellen's gentle prodding soon had him up and about again. Still, his mental and physical health remained below par; so in the spring of 1867 he and Ellen purchased a small farm in Greenville, Michigan, where she could more effectively implement her philosophy of useful labor for the sick. Although she was fairly successful in getting James to do simple chores about the garden, he rebelled at the prospect of bringing in the hay, hoping instead to rely on the good will of nearby friends. Ellen, however, outwitted him by getting to the neighbors first and persuading them not to help her husband when he came calling on them. Thus by hook or by crook she made sure James obtained the exercise she thought he needed.48

According to James, his sickness led Ellen to ease up for a while in her written and oral pronouncements on health reform. Nevertheless, personal hygiene remained one of her "favorite themes," and one she regarded as being as "closely connected with present truth as the arm is connected with the body."49 Meanwhile, during James's recuperation, exciting developments were under way in Battle Creek. There, in response to Mrs. White's Christmas vision, church leaders were laying plans to open the Western Health Reform Institute, a water cure modeled after Our Home and the first link in what was to become a worldwide chain of Seventh-day Adventist medical institutions.

Footnotes

- L. B. Coles, Philosophy of Health: Natural Principles of Health and Cure (rev. ed.; Boston: Ticknor, Reed, & Fields, 1853), p. 216.

- EGW, Christian Temperance and Bible Hygiene (Battle Creek: Good Health Publishing Co., 1890), p. 53.

- Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), pp. 161-62. Fitch's health reform activities are mentioned in Hebbel E. Hoff and John F. Fulton, "The Centenary of the First American Physiological Society Founded at Boston by William A. Alcott and Sylvester Graham," Institute of the History of Medicine, Bulletin, V (October, 1937), 704. On Hale, see Francis D. Nichol, The Midnight Cry (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1944), pp. 212-14.

- Daniel T. Taylor to Samuel F. Haven, August 7, 1861 (from a copy in the library of the Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, D.C.; original at the American Antiquarian Society); J. V. Himes, "My Sickness and Cure," Voice of the Prophets, II (January, 1861), 37-38; [Himes], "Two Important Books on Health," ibid., IV (January, 1863), 16; J. C. Jackson, "Morning Worship Talk-No. 1," Voice of the West, II (November 7, 1865), 176; "Good Words," Laws of Life, VIII (August, 1865), 122. John Himes and his wife also spent some time at Dansville; Obituary of John G. L. Himes, Advent Herald, XXV (July 26, 1864), 119.

- Joseph Bates, "Experience in Health Reform," HR, VI (July, 1871), 20-21. J. N. Loughborough, "Waymarks in the History of the Health Reform Movement," Medical Missionary, X (December, 1899), 6-7; John Harvey Kellogg, autobiographical memoir, October 21, 1938, and "My Search for Health," MS, January 16, 1942 (Kellogg Papers, MHC); R. F. Cottrell, "Experience in Health Reform," HR, VII (August, 1872), 251. See also W. C. White, "The Relationship of the White and Kellogg Families," MS. circa 1931 (DF 127g, White Estate). The pervasiveness of health-reform knowledge among Seventh-day Adventists is revealed by the fact that many members immediately noted the similarity between Mrs. White's views and those of Jackson and Trall; EGW, "Questions and Answers," R&H, XXX (October 8, 1867), 260.

- J. W. Clarke, "A Vegetarian Survives Disease without Drugs," HR, III (April, 1869), 194-95; Wm. McAndrew to Uriah Smith, February 11, 1857, R&H, IX (February 26, 1857), 135; S. N. Haskell, "What the Health Reform Has Done," HR, VI (July, 1871), 13; Mrs. Rebekah Smith, Poems: With a Sketch of the Life and Experience of Annie R. Smith (Manchester, N.H.: John B. Clarke, 1871), pp. 96-107; H. F. Phelps, "My Experience: No. 1," HR, II (March, 1868), 142-43; H. C. Miller, "Experience," HR, III (September, 1868), 52; "A Good Beginning," Laws of Life, VI (March, 1863), 43; "Good Words from the Readers of the Laws Received during the Month of March," ibid., VI (April, 1863), 53. See also "The People's Estimate of the 'Laws,'" ibid., VI (November, 1863), 176. In 1858 a Joseph Clarke recommended "Plain, coarse food at regular intervals, regular rest and exercise, habits of temperance in all things"; "Health," R&H, February 11, 1858), 106. I have been unable to prove that J. W. Clarke, Phelps, and Miller were Seventh-day Adventists, but it is likely that they were.

- James C. Jackson, "Diphtheria, Its Causes, Treatment and Cure," R&H, XXI (February 17, 1863), 89-91; James White, "Western Tour," R&H, XVI (November 13, 1860), 204. Jackson reprinted White's endorsement in the Laws of Life, VI (April, 1863), 64. How the Whites ran across Jackson's essay, first published in Penn Yan, New York, is not certain; it is possible that the newspaper clipping was sent to them by Elder John N. Andrews, an Adventist evangelist then preaching in western New York, who caught diphtheria during the 1863 epidemic and who was among the earliest sabbatarians to visit Our Home. See Diary of Mrs. Angeline Stevens Andrews, entry for February 17, 1863 (C. Burton Clark Collection).

- [James White], "Pure Air," R&H, XXI (February 10, 1863), 84; "What Is in the Bedroom?" ibid., p. 88. Portions of "What Is in the Bedroom?" are similar to passages in W. W. Hall, "Unhealthy Houses," Hall's Journal of Health, IX (June, 1862), 144; and Hall, Sleep; or The Hygiene of the Night (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870), p. 322.

- Dio Lewis, "Talks about Health," R&H, XXI (May 5, 1863), 179; W. W. Hall, "Spring Suggestions in Regard to Health," R&H, XXI (May 12, 1863), 185; [Hall], "Eating and Sleeping," R&H, XXI (May 19, 1863), 195. An earlier selection from Lewis appeared in 1862; "Talks about Health: A Word about Dress," R&H, XX (November 25, 1862), 203.

- J. H. Waggoner offered a similar interpretation in 1866. The Adventist contribution to health reform was not adding new knowledge, he said, but making it "an essential part of present truth, to be received with the blessing of God, or rejected at our peril." Waggoner, "Present Truth," R&H, XXVIII (August 7, 1866), 76-77.

- William C. White, "Sketches and Memories of James and Ellen G. White," R&H, CXIII (November 24, 1936), 3; Martha D. Amadon, "Mrs. E. G. White in Vision," November 24, 1925 (DF 105, White Estate); EGW, MS sermon, May 21, 1904 (MS-50-1904, White Estate). The date of the event is frequently given as June 6, because it occurred after sundown on June 5.

- Amadon, "Mrs. E. G. White in Vision"; EGW, MS relating the Vision of June 6, 1863 (MS-1-1863, White Estate).

- W. C. White, "Sketches and Memories," pp. 3-4; W. C. White, "The Origin of the Light on Health Reform among Seventh-day Adventists," Medical Evangelist, XX (December 28, 1933), 2.

- EGW, "Writing Out the Light on Health Reform" (MS-7-1867, White Estate); EGW, Spiritual Gifts: Important Facts of Faith, Laws of Health, and Testimonies Nos. 1-10 (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1864), pp. 120-51. An announcement for this fourth volume of Spiritual Gifts appeared in the R&H, XXIV (September 6, 1864), 120.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1864), pp. 120-51. The similarities between Ellen White and L. B. Coles can be seen in the following passages taken from EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1864), and Coles, Philosophy of Health (3rd ed.; Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1855): EGW, p. 128: Tobacco is a poison of the most deceitful and malignant kind, having an exciting, then a paralyzing influence upon the nerves of the body. Coles, p. 84: [Tobacco's] first influence is felt upon the nervous system. It excites and then deadens nervous susceptibility. EGW, p. 129: The whole system under the influence of these stimulants [tea and coffee] often becomes intoxicated. And to just that degree that the nervous system is excited by false stimulants, will be the prostration which will follow after the influence of the exciting cause has abated. Coles, p. 79: [Tea] is a direct, diffusible, and active stimulant. Its effects are very similar to those of alcoholic drinks, except that of drunkenness.... Like alcohol, it increases, beyond its healthy and natural action, the whole animal and mental machinery; after which there comes a corresponding languor and debility. EGW, p. 133: I was shown that more deaths have been caused by drug-taking than from all other causes combined. If there was in the land one physician in the place of thousands, a vast amount of premature mortality would be prevented. Multitudes of physicians, and multitudes of drugs, have cursed the inhabitants of the earth, and have carried thousands and tens of thousands to untimely graves. Coles, p. 207: It has been my settled conviction, for many years, as before stated, that there is more damage than good done with medicine... it has been, for many years, my belief that the standard of health and longevity of our land would now be far above its present position, if there had never been a single physician or a single drug in it.... Dr. Johnson says: "I declare my conscientious opinion... that if there were not a single physician, surgeon, apothecary, chemist, druggist, or drug, on the face of the earth, there would be less sickness and less mortality than now." Compare also Ellen White with Coles, The Beauties and Deformities of Tobacco-Using (rev. ed.; Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1855): EGW, p. 126: [Tobacco] affects the brain and benumbs the sensibilities, so that the mind cannot clearly discern spiritual things.... Coles, p. 97: [Tobacco-users] so deaden the natural sensibilities of body and mind, by using it, that they are not immediately susceptible of the impulses of the Holy Spirit, by which alone a true spirit of devotion and religious enjoyment are induced.

- Ibid., pp. 129-30, 133-40, 142-45.

- W. C. White, "Sketches and Memories," p. 4; EGW, "Writing Out the Light on Health Reform"; EGW, "Questions and Answers," p. 260.

- EGW, "Writing Out the Light on Health Reform"; James C. Jackson to James White, August 13, 1863 (White Estate); J[ames] W[hite], "The Health Reform," R&H, XXV (December 13, 1864), 20.

- J[ames] W[hite], "The Health Reform," p. 20; J. V. Himes, "Two Important Books on Health," pp. 16-17. The pamphlet by Jackson was How to Treat the Sick without Medicine (Dansville, N.Y., 1862). In an attempt to harmonize the statements of James and Ellen White, Ron Graybill of the White Estate has suggested "that James called her attention to the ad in Voice of the Prophets during their stay in Boston in September of 1863 and stated to her that he had ordered these books. She could easily have assumed that he meant that he had ordered them on that occasion — September of 1863 — when in fact he had ordered them earlier." (Ron Graybill to the author, March 11, 1975.) This explanation raises the question of why James made no effort to correct Ellen's wrong impression when the true sequence of events was so important an issue.

- James White to Ira Abbey, December 12, 1863 (White Estate); [J. C. Jackson], "Which Will You Have, Hoops or Health?" R&H, XXII (October 27, 1863), 176. Although James White was editor of the Review and Herald in 1863, he was traveling in the East when Jackson's article appeared in October. During the second half of 1863 the Review and Herald carried several other articles on health reform that Ellen White probably read before writing out what she had seen in her June 5 vision: "Keep Your Teeth Clean," R&H, XXII (July 28, 1863); Dio Lewis, "How to Prevent Colds," R&H, XXII (August 4, 1863), 75; Lewis, "Eating when Sick," R&H, XXII (August 11, 1863), 86-87; Lewis, "Talks about Health: A Word to My Fat Friends," R&H, XXII (August 25, 1863), 98-99; W. T. Vail, "Eating and Sleeping," R&H, XXIII (December 8, 1863), 11.

- EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1864), pp. 153-54; EGW, Testimonies, II, 371-72.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," R&H, XXVII (February 27, 1866), 97; EGW, Spiritual Gifts (1864), pp. 151-53; Dores E. Robinson, The Story of Our Health Message (3rd ed.; Nashville: Southern Publishing Assn., 1965), pp. 86-87; EGW, "That Spare Bed," HR, IX (February, 1874), 41.

- R. F. Cottrell, "Oh, Yes, I See It Is So," HR, I (February, 1867), 105. For what it meant to be an Adventist health reformer, see the scores of testimonials in the early volumes of the Health Reformer.

- M. D. Amadon, "How to Use Graham Flour," R&H, XXIV (November 1, 1864), 178-79; EGW, MS-27-1906, quoted in EGW, Counsels on Diet and Foods (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1938), p. 442.

- Diary of Mrs. Angeline Stevens Andrews, October, 1859, to January, 1865 (C. Burton Clark Collection); J. N. Andrews, "My Experience in Health Reform," HR, IV (July, 1869), 8-10, VII (February, 1872), 44-45, VII (March, 1872), 76-77; Daniel T. Taylor, "Sabbatical Library for Sale," advertisement included with a letter to S. F. Haven, January 26, 1863 (from a copy in the library of Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, D.C.; original at the American Antiquarian Society). Andrews's role in introducing the Adventists to Dansville is mentioned in D. M. Canright, "Progress of Health Reform," HR, XIII (May, 1878), 133; and G. I. Butler to John Harvey Kellogg, March 7, 1906 (Kellogg Collection, MSU). The Andrewses may have learned about the Dansville water cure from Marietta V. Cook, a friend of theirs.

- Jackson to White, August 13, 1863; Diary of Mrs. Andrews; James White, "Eastern Tour," R&H, XXIV (November 22, 1864), 205; EGW to Edson and Willie White, June 13, 1865 (W-3-1865, White Estate). A search of the Dansville Advertiser and the Herald for 1864 and 1865 turned up no mention of the Whites. Mr. William D. Conklin, of Dansville, kindly assisted me in going through these newspapers.

- Adelia P. Patten to Sister Lockwood, September 15, 1864 (White Estate).

- EGW to Bro. and Sister Lockwood, September [14], 1864 (L-6-1864, White Estate); James C. Jackson, "Description of Character of Willie C. White ... Sept. 14, 1864" (DF 783, White Estate). According to the testimony of a disaffected Adventist in Iowa, Mrs. White herself stated in 1865 that Jackson had "pronounced her a subject of Hysteria"; H. E. Carver, Mrs. E. G. White's Claims to Divine Inspiration Examined (2nd ed.; Marion, Iowa: Advent and Sabbath Advocate Press, 1877), pp. 75-76. Jackson apparently began giving "psycho-hygienic examinations of character" early in 1864; see his advertisement in Laws of Life, X (January, 1867), 15.

- EGW to Bro. and Sister Lockwood, September [14], 1864.

- Adelia P. Patten to Sister Lockwood, September 15, 1864.

- Ibid. Ellen was not the first visitor to be disturbed by Jackson's advocacy of "worldly" amusements. The Rev. John D. Barnes, a Union chaplain who recuperated at Our Home in the summer of 1862, recalled being approached by "a delegation of long faced very serious looking men," who wanted him to sign a petition protesting the dancing and card playing. He refused, to Jackson's great delight. John D. Barnes, MS Autobiographical Memoir (Huntington Library, San Marino, California). This document was brought to my attention by Wm. Frederick Norwood.

- Diary of Mrs. Andrews; EGW to Edson and Willie White, June 13, 1865; J. N. Loughborough, "Report from Bro. Loughborough," R&H, XXV (December 6, 1864), 14; [Uriah Smith], The Visions of Mrs. E. G. White (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1868), p. 85.

- EGW, Letter 45, 1903, quoted in Arthur L. White, Ellen G. White: Messenger to the Remnant (Washington: Review and Publishing Assn., 1969), p. 106; EGW, Health; or, How to Live (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1865); James White, "The Health Reform," R&H, XXV (December 13, 1864), 20. In 1860 Fowler & Wells published a book entitled How to Live, by Solon Robinson. Ellen probably saw the title in Dio Lewis, Weak Lungs, and How to Make Them Strong (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1863), p. 114, a volume she was reading at the time.

- EGW, How to Live, No. 1, pp. 31-51.

- EGW, "Questions and Answers," p. 260; John H. Kellogg, autobiographical memoir, October 21, 1938; "Interview between George W. Amadon, Eld. A. C. Bourdeau, and Dr. J. H. Kellogg, October 7, 1907," and J. H. Kellogg to E. S. Ballenger, January 15, 1929 (Ballenger-Mote Papers). In her How to Live essays Ellen White incorporated some ideas that had recently appeared in the Review and Herald. Compare, for example, her comments on the necessity of clothing the arms of babies (No. 5, p. 68) with Dio Lewis, "Talks about Health," p. 203; or her advice on two meals a day (No. 1, pp. 55-57) with [W. W. Hall], "Eating and Sleeping," p. 195.

- R. F. C[ottrell], "Our New Publications," R&H, XXVI (October 10, 1865), 148; J. N. Andrews, "How to Live," ibid., XXVI (September 12, 1865), 116; EGW, "Feeding of Infants," ibid., XXXI (April 14, 1868), 284; James White, "Health Reform No. 4: Its Rise and Progress among Seventh-day Adventists," HR, V (February, 1871), 152.

- General Conference Committee, "God's Present Dealings with His People," R&H, XXVII (April 17, 1866), 156; U[riah] S[mith], "Notes by the Way. No. 2," ibid., XXVI (October 3, 1865), 140.

- "Sickness of Bro. White," R&H, XXVI (August 22, 1865), 96; H. S. Lay, "Eld. White and Wife, and Eld. Loughborough," ibid., XXVI (October 31, 1865), 172; EGW, "Our Late Experience," pp. 89-91; EGW, "Recreation for Christians," Testimonies, I, 518; EGW, Life Sketches of Ellen G. White (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1915), pp. 167-68.

- R&H, XXVI (September 19, 1865), 128; Smith, "Notes by the Way," p. 140.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," R&H, XXVII (February 20, 1866), 89-91, (February 27, 1866), 97-99; EGW to Edson White, October 19, 1865 (W-7-1865, White Estate); EGW, "The Sickness and Recovery of Elder James White," circa 1867 (MS-1-1867); D. T. Bourdeau, "At Home Again," R&H, XXVI (November 14, 1865), 192.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," p. 89; EGW to Edson and Willie White, September 22, 1865 (W-6-1865, White Estate). For James White's apology, see "Report from Bro. White," R&H, XXIX (January 22, 1867), 74.

- "Bro. White's Sickness," R&H, XXVI (October 3, 1865), 144; U[riah] S[mith], "Notes by the Way. No. 3," ibid., XXVI (October 24, 1865), 164; J. N. Loughborough, "Note," ibid., XXVI (October 31, 1865), 176; EGW, "Our Late Experience," p. 97.

- EGW to James White, November 22 and 24, 1865 (W-9-1865, W-10-1865, White Estate); Adelia P. Van Horn, "A Word from Dansville, N. Y.," R&H, XXVI (November 21, 1865), 200.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," p. 97.

- Ibid., pp. 90, 97-98; EGW, "The Sickness and Recovery of Elder James White"; EGW to Brother Aldrich, August 20, 1867 (A-8-1867, White Estate). On amusements at Dansville, see also Smith, "Notes by the Way. No. 3," p. 164. Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, described the dances at Our Home in a letter to Jere Learned, July 15, 1876: "There is an amusement society, and one of its features is a beautiful dance once a week from 5 till 8 P.M. Piano and violin music - no round dances but cotillions and all dances which are not injurious, and the prettiest and most elegant dancers in the hall are from among the help." Quoted in William D. Conklin, The Jackson Health Resort (Dansville, N.Y.: Privately distributed by the author, 1971), p. 184.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," pp. 97-98; EGW, "The Sickness and Recovery of Elder James White"; EGW, Life Sketches (1915), pp. 170-71.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," pp. 91, 98; EGW, "The Health Reform," Testimonies, I, 485-93; EGW, "Health and Religion," ibid., I, 565. Ellen White's Christmas vision in Rochester was truly seminal. In addition to revealing the prospects for James White's recovery and the need for an Adventist water cure, it prompted testimonies on subjects as diverse as the taking of usury, erroneous political views, Sabbath observance, the Adventist cause in Maine, the duties of parents, the business interests of ministers, and the spiritual condition of several brethren and sisters. See Comprehensive Index to the Writings of Ellen G. White (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1963), III, 2980.

- EGW, "Our Late Experience," pp. 98-99; "Bro. White at Home," R&H, XXVII (January 9, 1866), 48; D. E. Robinson, The Story of Our Health Message (Nashville: Southern Publishing Assn., 1955), pp. 161-66.

- James White, "Western Tour: Kansas Camp-Meeting," R&H, XXXVI (November 8, 1870), 165; James White, "Report from Bro. White," ibid., XXVIII (June 19, 1866), 20; EGW to Brother Aldrich, August 20, 1867.