Prophetess of Health

Chapter 5: The Western Health Reform Institute

By Ronald L. Numbers

"More deaths have been caused by drug-taking than from all other causes combined. If there was in the land one physician in the place of thousands, a vast amount of premature mortality would be prevented."

Ellen G. White1

"Were I sick, I would just as soon call in a lawyer as a physician from among general practitioners. I would not touch their nostrums, to which they give Latin names. I am determined to know, in straight English, the name of everything that I introduce into my system."

Ellen G. White2

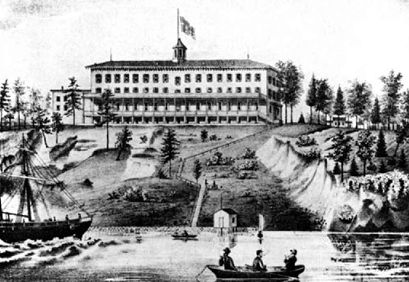

September 5, 1866, marked the fulfillment of one of Ellen White's fondest hopes: the grand opening of the Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek. Since her first visit to Dansville in the fall of 1864, she had dreamed of founding an Adventist water cure where Sabbath-keeping invalids could receive treatments in an atmosphere compatible with their distinctive faith. Her disillusionment with Our Home during James's illness and the subsequent Christmas vision of 1865 convinced her that the time had finally arrived to take positive action. Vigorous support came from the denomination's leaders, especially the numerous Dansville alumni, who shared her enthusiasm for an Adventist medical center. Uriah Smith, the influential editor of the Review and Herald, regarded his few weeks at Our Home as one of the most valuable experiences of his life and saw the establishment of a similiar institution in Battle Creek as "a present necessity," both for treating the sick and for educating the church in the principles of health reform. Thus while politicians in Washington quarreled bitterly over the best method of healing a divided and scarred nation, the Adventists of Battle Creek dedicated themselves to curing mankind with water.3

At the annual General Conference session in May, 1866, attended by church representatives from throughout the country, Ellen White announced the Lord's instruction to establish an Adventist water cure. The response was immediate and favorable. In the absence of the recuperating James White, John Loughborough, president of the Michigan conference, assumed overall responsibility for the fund-raising drive and took personal charge of the campaign in the West. John Andrews, another Dansville man, directed operations in the East, while the remaining ministers at the conference volunteered to serve as agents, selling stock in the proposed institute at twenty-five dollars a share. As soon as sufficient funds were on hand, arrangements were made to purchase an eight-acre site on the outskirts of town. Although existing buildings on the property could accommodate up to fifty patients, it was necessary to build an additional two-story structure to house a "packing room, bath room, dressing room, and a room to contain a tank of sufficient capacity to hold two hundred barrels of water."4

The plans to pour large sums of money into a water cure led some members to question the judgment of the brethren in Battle Creek. For years Mrs. White had been warning against heavy investments in this world, and the establishment of a big, permanent medical facility struck the critics as nothing less than "a denial of our faith in the speedy coming of Christ." To squash such sentiments, both Elders Loughborough and D. T. Bourdeau (still another former patient of Our Home) took to the pages of the Review and Herald to point out that the Health Reform Institute, far from being a denial of faith, would be the means of "bringing thousands to a knowledge of present truth." The institute, Loughborough predicted, "will fill its place in this cause, from the fact that scores who come to it to be healed of temporal maladies, who learn the lesson of self-denial to gain health, may also, by being brought into a place where they become acquainted with the character and ways of our people, see a beauty in the religion of the Bible, and be led into the Lord's service."5

Circulars describing the Western Health Reform Institute went out to all Adventist churches and potential stockholders and appeared in the Review and Herald as well. "In the treatment of the sick at this Institution," read the announcement,

no drugs whatever, will be administered, but only such means employed as NATURE can best use in her recuperative work, such as Water, Air, Light, Heat, Food, Sleep, Rest, Recreation, &c. Our tables will be furnished with a strictly healthful diet, consisting of Vegetables, Grains, and Fruits, which are found in great abundance and variety in this State. And it will be the aim of the Faculty, that all who spend any length of time at this Institute shall go to their homes instructed as to the right mode of living, and the best methods of home treatment.

In language typical of American nostrum vendors, prospective patients were glibly assured that "WHATEVER MAY BE THE NATURE OF THEIR DISEASE, IF CURABLE, THEY CAN BE CURED HERE." All bills were to be paid in advance, and individuals unable to visit the institute in person could receive a prescription by letter for five dollars, the same fee charged for a personal examination.6

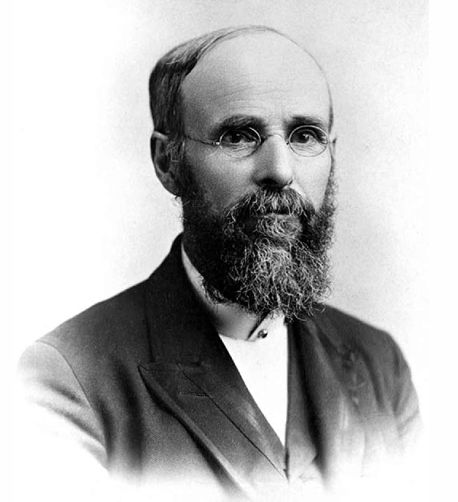

Horatio S. Lay

Chief physician at the institute, and one of the few Adventists with medical experience of any kind, was thirty-eight-year-old Horatio S. Lay, a man "thoroughly conversant with the latest and most approved Hygienic Methods of Treating Disease." As a youth Lay had apprenticed himself to a local doctor in Pennsylvania and acquired the fundamentals of the trade. In 1849, feeling sufficiently knowledgeable to assume the title of doctor, he moved to Allegan, Michigan, a small town northwest of Battle Creek, and began practicing as an allopathic physician. About 1856 he joined the Seventh-day Adventists, and a few years later became interested in the health-reform movement. Following Ellen White's 1863 vision on health, it was Lay who first drew her out on the subject and who informed her of the remarkable similarity between her revelation and the teachings of the health reformers.7

Shortly after his conversations with Mrs. White, Lay took his consumptive wife to the Dansville water cure, a move the prophetess saw in vision as being providentially arranged to train him for future work as a health reformer. At Dansville he quickly won the respect of the hydropaths. He was invited to join the staff of Our Home and in 1865 was elected a vice-president of the National Health Reform Association (along with Joshua V. Himes). During this time he toyed with the idea of "of going to N. York City to Dr. Trall's college and attend lectures, obtain a diploma and come out a regular [sic] M.D.," but he never went. In fact, it was not until 1877, long after he had severed his ties with Battle Creek, that he finally attended school and received an authentic medical degree from the Detroit Medical College.8

The Western Health Reform Institute was a booming success. Within months of its opening patients from all over the country filled its rooms to overflowing. But prosperity also bred problems: the need for additional space and trained personnel. During the first years of the institute Lay seems to have been the only member of "the Faculty" with significant medical experience, and even he had never seen the inside of a medical school. Several others on his staff called themselves doctors, but the term was loosely used in those days. The institute's lady physician, Phoebe Lamson, had spent some time at Dansville with her ailing father and may have picked up a rudimentary knowledge of hydropathic medicine. To qualify herself more fully "to act her part in the Institution," she obtained Ellen White's permission to spend the winter 1867-68 term at Trall's Hygeio-Therapeutic College in New Jersey and returned a few months later proudly displaying an "M.D." after her name.9

The Health Reformer

In addition to his duties at the Health Reform Institute, Lay took on the editorship of a new monthly journal, the Health Reformer. During the summer of 1865, while still at Dansville, he had furnished the Review and Herald with a series of essays on "Health," outlining the main tenets of the reform movement. The church leaders liked his work so well that they voted at the next general conference session to have him write a second series on the same topic. But before any of his articles appeared, they ambitiously decided instead to have Lay edit "a first class Health Journal, interesting in its variety, valuable in its instructions, and second to none in either literary or mechanical execution." According to the prospectus, the journal was to be nondenominational in orientation and dedicated to curing diseases "by the use of Nature's own remedies, Air, Light, Heat, Exercise, Food, Sleep, Recreation, &c."10

The first issue of the Reformer came off the press in August, 1866, carrying the motto "Our Physician, Nature: Obey and Live." Though distinctly second class in literary quality, it was an attractive publication by nineteenth-century standards. Because of the dearth of medical writers in the church, most articles were from the pens of ministers like Loughborough, Andrews, and Bourdeau. Even Ellen White contributed a composition, "Duty to Know Ourselves," based on L. B. Coles's theme that to break one of the laws of life is "as great a sin in the sight of Heaven as to break the ten commandments." To avoid charges of religious sectarianism, the editors of the Reformer printed little by or about the Adventist seer in the first several volumes. Nevertheless, Mrs. White had high hopes for the magazine. "The Health Reformer is the medium through which rays of light are to shine upon the people," she wrote in an 1867 testimony. "It should be the very best health journal in our country."11

Among the most readable features of the Reformer were the "Question Department," where readers' queries on home treatment were answered, and numerous testimonials to the curative powers of health reform. Although the medical men in Battle Creek were prone to complain of apathy among the membership as a whole, glowing reports of how two meals a day and no butter had restored health and strength filled the pages of the Reformer. Typical was the progressive reform of Brother Isaac Sanborn, president of the Illinois-Wisconsin conference, who for years had suffered painfully from "inflammatory rheumatism":

I concluded I would leave off the use of meat, which I did by leaving pork first: then beef, then condiments, fish, and mince pies. Then I adopted the two meals a day, had breakfast at seven A.M., and dinner at half past one P.M.; used no drug medicines of any kind, lived on Graham bread, fruit and vegetables, using no butter, but a little cream in place of butter. I drink nothing with my meals, and I relish and enjoy my meals as I never have before; and the result is, I am entirely well of the rheumatism, which I used to have so bad by spells that I could not walk a step for days; and although I travel through all kinds of weather, and speak often in crowded assemblies, in ill-ventilated schoolhouses, and am exposed in various ways, yet I have not had a bad cold for more than two years.12

Throughout its early history the Reformer exuded antipathy toward regular medicine, leaving no doubt of the medically sectarian loyalties of its Battle Creek promoters. This hostility reflected not only a genuine distrust of orthodox physicians but also deep-seated feelings of inferiority. "Some people seem to think that nobody can talk on Health but an M.D., and nobody on Theology but a D.D.," wrote the self-conscious and degreeless editor. "But how ever much there is in a name, or in a title, everybody will admit that all knowledge of health should not be left with the doctors, nor all theology with the ministers." J. F. Byington, Lay's associate at the institute, became almost vitriolic in denouncing the "old school," calling its therapy a "terrible humbug" and its practitioners "too bigoted and self-conceited to learn." Even the Whites were not much kinder. Ellen charged "popular physicians" with deliberately keeping their patients in ignorance and ill-health for monetary reasons, while James ridiculed "the superstitious confidence of the people in doctors' doses." Ironically, these bitter attacks on the regular medical profession came at the very period when that school was finally abandoning its long-practiced customs of bloodletting and calomel-dosing.13

For several months the future of the fledgling Battle Creek health institutions looked bright indeed. But it was not long before ominous storm clouds rolled in, casting shadows not only on the institute and the Reformer, but on Ellen White herself. The first episode began innocently in January, 1867, with an announcement by Dr. Lay that the institute was already filled to capacity and would soon be turning away incoming patients for lack of room. "What shall be done?" he inquired of readers in the Review and Herald. His own answer was to erect at once an additional "large" building capable of housing "at least one hundred more patients than we now have." The estimated cost was twenty-five thousand dollars — a figure seven times the General Conference budget for that year.14

Before the month was out, Uriah Smith had thrown the weight of the Review and Herald behind the project, and interest in Lay's proposal was running high in Adventist circles. The immediate problem, as the institute's backers saw it, was how to gain a public endorsement from Mrs. White. One solution came from John Loughborough, who had just returned from a trip with Ellen and had heard her give a "good testimony" regarding the institute and its superintendent. Why not, he suggested, ask her to write out this message for Testimony No. 11, then going to press. This plan met with general approval, and Smith was nominated to carry out the assignment.15

The Ill-Fated Testimony

On February 5 Smith sent a letter to Mrs. White urging her to sanction additional investments in the institute. He reminded her that a widely distributed circular had promised a statement in her next Testimony relative to the medical work in Battle Creek and pointed out that such a communication would be expected:

... a great many are waiting before doing anything to help the Institute, till they see the Testimony and now if it goes out without anything on these points, they will not understand it, and it will operate greatly against the prosperity of the Institution. The present is a most important time in this enterprise, and it is essential that no influence should be lost, which can be brought to bear in its favor.

In closing he offered to hold up the printing of the last pages of Testimony No. 11 until she could rush her manuscript to him. Then, as if he had not already prompted her enough, the brash young Smith went on to add a postscript suggesting that she particularly emphasize the connection between the health work and "the cause of present truth." We think, he said, this relationship "should be made plainly to appear."16

Thus prodded, Ellen White hurriedly wrote out the desired testimony. First, following Smith's suggestion, she commented on the intimate relationship between theology and health: "The health reform, I was shown, is a part of the third angel's message [that is, Seventh-day Adventism], and is just as closely connected with it as are the arm and hand with the human body." Then, after describing the Battle Creek water cure, she stated that God had shown her in vision that the institute was "a worthy enterprise for God's people to engage in, one in which they can invest means to his glory and the advancement of his cause." Institutions like that in Battle Creek could play a vital role in directing "unbelievers" to Adventism, for by "becoming acquainted with our people and our real faith, their prejudice will be overcome, and they will be favorably impressed." Here was "a good opportunity," she advised, for those with financial security "to use their means for the benefit of suffering humanity, and also for the advancement of the truth."17

Given this divine blessing — and the fact that investments were rumored to be returning an annual dividend of 10 percent — institute stock enjoyed healthy sales throughout the spring and summer months. By mid-August the basement and first floor of the new building were completed, and lumber was on hand for the remaining three stories. But the money had run out. While construction was temporarily halted, the directors of the institute appealed once again to the church membership, urging them to recall Mrs. White's counsel in Testimony No. 11 and buy more shares in the institution.18

Revising the Testimony

Though the directors undoubtedly did not know it, Mrs. White was at that time preparing to back away from her previous endorsement of the expansion plans. Her private correspondence reveals that by August she was having qualms that the institute might be growing too rapidly for a man of Lay's limited abilities. "Dr. Lay is not qualified to carry on so large a business as you are laying out for him," she cautioned one of the institute's directors. "Dr. Lay has done well to move out in this great work, but he can bear no heavier burdens." In addition to Lay's limitations, she and her husband feared that the institute's supporters were moving too fast too soon, given the available money and personnel. Some poor Adventists, she pointed out, were taking unsound financial risks, putting "from one-fifth to one-third of all they possess into the Institute." In response to these and other problems, by mid-September she had prepared Testimony No. 12 modifying her earlier statements in Testimony No. 11. Now, she said, the Lord had shown her that the institute should be "small at its commencement, and cautiously increased, as good physicians and helpers could be procured and means raised." She pointed out, correctly, "that out of many hygienic institutions started in the United States within the last twenty-five years, but few maintain even a visible existence at the present time."19

This virtual repudiation of what the church considered to be a divinely inspired testimony demanded an explanation. Uncharitable critics later hinted that James had been behind the change, but Ellen placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of Uriah Smith and his associates. Smith's importunate letter of February 5 had caused her mental suffering "beyond description," she explained. "Under these circumstances I yielded my judgment to that of others, and wrote what appeared in No. 11 in regard to the Health Institute, being unable then to give all I had seen. In this I did wrong." Still, she refused to withdraw "one sentence" from what she had written in Testimony No. 11, admitting only that she had acted prematurely. Her lament that the entire affair had been "one of the heaviest trials" of her life surely evoked only sympathy. Yet her admitted wavering under pressure raised long-lasting questions about her susceptibility to human influences.20

Testimony No. 12 apparently caught the institute's directors by surprise. The secretary, E. S. Walker, immediately wrote James White protesting that "it would require a great amount of labor and be attended with considerable expense to undo what we have already done." The directors, he said, thought it best to proceed as soon as possible with putting a roof over the new building and then to complete the interior as funds became available. To do this, they needed the Whites' public approval. On behalf of the directors he promised a reform in the management of the water cure, so that the Whites could once again "feel to work for the Institute as [they] did at its commencement."21

Reversing the Testimony

But James White did not back down. Instead, a very strange thing happened — "a real hocus pocus," remembered one old-timer. At White's insistence, and apparently with the concurrence of at least two directors, the entire structure was torn down stone by stone until not a trace remained where shortly before there had stood the proud beginning of a new sanitarium. Some placed the loss at eleven thousand dollars, but a portion of this sum was undoubtedly recovered through the sale of salvageable materials. The complex motives behind this seemingly irrational act will never be fully known. Years after the event, John Harvey Kellogg discussed the incident with White and concluded that the building had been razed "for no other reason than because James White was not consulted" at the time of its planning. By then the aging elder had come to regret his impetuous decision and confided to the young doctor that "if I had known how much power and strength there was in this thing, I never would have torn that thing down."22

At no time during this unpleasant episode did Ellen White allude in print to her husband's erratic behavior. Although privately concerned for his mental health during this period of his life, she publicly defended him as a man chosen of God and given "special qualifications, natural ability, and an experience to lead out his people in the advance work." James himself, instead of apologizing for throwing away the institute's money, condescendingly appealed to the church to forgive the men in Battle Creek "who have moved rashly, and have committed errors in the past for want of experience." The "large building is given up for the present, and the material is being sold," he announced matter-of-factly in the Review and Herald a month after his election in May, 1868, to the institute's board of directors. Then, after complaining of the large debt recently incurred, he audaciously went on to request thirteen thousand dollars for a modest two-story building and two cottages, a figure just two thousand dollars shy of what it would have cost to finish the original structure. "Send in your pledges, brethren, at once, and the money as soon as possible," he urged. "It is a SAFE INVESTMENT."23

To Ellen White, the extravagant plans for physical expansion were only the tip of the iceberg threatening the institute. Much more disturbing were the ubiquitous signs of worldliness: patients and staff enjoying Dansville-style amusements, physicians demanding higher wages than ministers, and workers calling each other "Mister" and "Miss" rather than "Brother" and "Sister." (Until the 1880s some Adventists refused even to use the common, but pagan, days of the week, substituting instead First-day, Second-day, etc.)24

The institute directors considered amusements, "when conducted within proper limits, as an important part of the treatment of disease." Their celebration of the first Thanksgiving at the water cure included songs, charades, pantomime, nonalcoholic toasts, and attempts at poetry:

Hoops on barrels, tubs, and pails,

Are articles indispensable;

But hoops as they puff out woman's dress,

Making the dear women seem so much less,

Are most reprehensible.

Such activities upset Mrs. White, especially since the Western Health Reform Institute had been established precisely to get away from such unchristian practices. And the topic became personally embarrassing when reports began circulating that Ellen White herself had taken to occasional game playing. Is it true, inquired some Adventist elders, "that you have taken an interest in the amusements which have been practiced at the Health Institute at Battle Creek, that you play checkers, and carry a checker-board with you as you visit the brethren from place to place?" Absolutely not, she replied in the Review and Herald. Since her conversion at the age of twelve she had forsaken all such frivolities as checkers, chess, backgammon, and fox-and-geese. "I have spoken in favor of recreation, but have ever stood in great doubt of the amusements introduced at the Institute at Battle Creek, and have stated my objections to the physicians and directors, and others, in conversation with them, and by numerous letters."25

By the fall of 1867 Ellen White was so disgusted with the health institute she regarded it as "a curse" to the church, a place where sincere Christians became infidels and believers lost faith in her testimonies. But later that year a spiritual revival swept through the Adventist community in Battle Creek and rekindled her enthusiasm for the water cure. The following spring she pledged renewed support, and James became a director. Her blessing and her husband's business acumen were not sufficient, however, to keep the institute solvent. By the autumn of 1869 only eight paying patrons remained. A surplus of charity patients and other factors had contributed to this situation, but so had Mrs. White's harsh criticisms that had tarnished the institute's reputation among Adventists. She naturally saw it differently and later blamed the institute's decline entirely on the managers, especially Dr. Lay, whom she had come to regard as too proud and self-centered for his position. The directors at their 1869 annual meeting meekly acknowledged their guilt and absolved the Whites of any culpability. Within a year Dr. J. H. Ginley had replaced the unfortunate Dr. Lay as superintendent, and businessmen had taken the place of the ministers on the board of directors.26

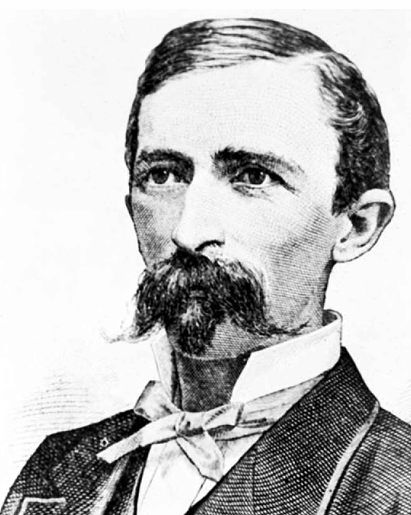

Merritt Kellogg

At the height of the institute controversy Merritt Kellogg paid the Whites a surprise visit. The former Oberlin student, now in his mid-thirties, was on his way back to California after attending the winter term at Trall's Hygeio-Therapeutic College and picking up an M.D. degree. The Whites, ever suspicious of close contacts with outsiders, fully expected that someone so "fresh from Dr. Trall's school" would be polluted with extreme and objectionable views. They were "happily disappointed," however, to discover that Kellogg was free from all such fanaticism. And they were delighted when he explained the remarkable harmony between what the Lord had revealed to Ellen White and what Trall taught his students. Here was just the man, thought James, to go around to the churches and revive flagging interest in health reform.27

At first the unknown Kellogg merely accompanied the Whites on their speaking tours, presenting the scientific side of the reform question. But at the May General Conference session, through the influence of Elder White, the church officers asked Kellogg to remain in the East as a full-time health lecturer, speaking to local churches upon request. Kellogg agreed to this arrangement, but after only three series of talks in small Michigan towns, no more invitations came in. Disheartened, he wrote Mrs. White complaining of this strange "dumbness" on the part of the churches "after so much has been shown in vision concerning the importance of this health movement." He felt the Whites had already said more than enough in his behalf, and he refused "to beg the privilege of lecturing." When still no calls came, the discouraged man returned to his home in California and joined an evangelistic campaign.28 Kellogg's few months in Michigan did produce one significant result: a union between the Battle Creek reformers and Dr. Trall, the foremost American hydropath. Undoubtedly inspired by Kellogg's favorable account of Trall's teachings, the Whites arranged to bring the prominent health reformer to Battle Creek for a course of lectures at the close of the annual general conference meetings. After an opening address to the conference delegates on Sunday evening, May 17, Trall spoke twice a day for four days to somewhat smaller crowds that included many Adventist ministers in town for the conference. Thursday afternoon was reserved for a private meeting with women only and was attended by hundreds of ladies attired in the reformed "short" dress. This display of the costume, the greatest Trall had ever seen, he credited to the influence of Mrs. White, who "not only advocates the dress-reform, but practices it."29

Dr. Trall

The only account we have of Trall's relationship with Ellen during this visit is curious indeed. Years after the event John Loughborough (a sometimes unreliable witness) wrote that although Ellen had refused to attend Trall's public lectures she had invited him on daily carriage rides during which "it was understood that he was to listen to her ideas of hygiene, disease and its causes, the effects of medicines, etc." After the second day's conversation Trall reportedly asked her where she had studied medicine and was told she had received all her information from God in vision. "He assured her that her ideas were all in the strictest harmony with physiology and hygiene, and that on many of the subjects she went deeper than he ever had." By their last session together the amazed doctor is supposed to have remarked that his hostess could just as well have given the lectures on health as he. At least this is what Loughborough claimed to have heard from John Andrews, who rode along with the Whites and Trall through the streets of Battle Creek.30

The rapport thus established between the Whites and Trall resulted in the doctor's being asked to become a regular contributor to the Reformer. The addition of a distinguished name — "admitted by all to stand at the head of the health reform in this country, so far as human science is concerned" — was calculated to pump new life into an unexciting publication and was part of an overall plan of James White's for revamping the journal. Beginning with the first issue of the third volume (July, 1868), the number of pages was increased, a disgraced Lay was replaced by an "Editorial Committee of Twelve," and Trall's "Special Department" was inaugurated. For his part, Trall cooperated by folding his monthly Gospel of Health and turning over its subscription list to the Reformer, with the assurance to his readers that it would "be managed by those who are, head and heart, in full sympathy with the true principles of the great health reformation." With this merger Battle Creek for the first time assumed national importance in the health-reform movement.31

The new arrangement, begun with such high hopes, proved to be less than ideal. Numerous readers, it soon turned out, resented Trall's strictures against the use of salt, milk, and sugar. And to make matters worse, the managing editor of the Reformer, known by insiders to use these articles of food himself, backed Trall editorially and thus prompted the pioneer reformer to speak out stronger than he otherwise would have done. The Whites, who personally respected Trall's opinions on diet, first detected signs of discontent while on a speaking tour through some Western states. There they found that many Westerners regarded the Reformer as "radical and fanatical" and had no interest at all in becoming subscribers. Upon returning to Battle Creek the dismayed Whites learned that letters were pouring in from disgruntled readers canceling their subscriptions. Clearly, the journal was "going away from the people, and leaving them behind."32

No doubt encouraged by Ellen, James assumed the helm of the Reformer himself and pledged to steer a course away from all extremes. Trall, however, stayed. His department alone was, in the elder's opinion, "worth twice the subscription price of the Reformer." During his illness in the mid-1860s James White had given up milk, salt, and sugar, and he believed "the time not far distant" when Trall's position on the use of these items would "be looked upon by all sound health reformers with more favor than they are at the present time." To placate disgruntled subscribers, and to give the journal an air of doctrinal orthodoxy, James had Ellen begin a second "Special Department" in the March, 1871, issue, at the same time warning readers not to "feel disturbed on seeing some things in these departments which do not agree with their ideas of matters and things." Even without the sections by his wife and Dr. Trall, there were "pages enough where all can read tenfold their money's worth." With Ellen's monthly department, regular articles by James, and advertisements for son Willie's "Hygienic Institute Nursery," the new Reformer at times took on the appearance of a White family production.33

Whatever his personal problems, James White was an effective promoter. Within two years he had raised subscriptions to the Reformer from three thousand to eleven thousand, and by 1875 an official report showed it to have "by far the largest circulation of any journal of its kind in the world." The previous year both special departments, having served their purpose, were discontinued. The fact that Trall left the Reformer at the height of its success, and apparently with the Whites' blessing, gives the lie to later charges by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg that Trall was responsible for the magazine's earlier difficulties.34

By the early 1870s the financial outlook of the institute and the Reformer appeared fairly bright; yet a dire shortage of Adventist physicians continued to threaten the medical work. Before there could be any significant expansion, it was obviously necessary, said James White, to "Hustle young men off to some doctor mill."35 As far as Adventist needs were concerned, the best "mill" was Trall's Hygeio-Therapeutic College in Florence Heights, New Jersey, where the medical course was not only hydropathic but quick.

Although Trall's school may have been one of the weakest in America, it had many competitors. As Dr. Thomas L. Nichols remarked in 1864, Americans did everything in a hurry, including the training of their physicians:

Nominally it is required that the student shall read three years, under some regular physician, during which time he must have attended two courses of medical lectures. If, however, he pay his fees, exhibit a certificate as to the time he has studied, or pretended to study, and pass a hasty examination, made by professors who are very anxious that he should pass, he gets a diploma of Medicinae Doctor. He has full authority to bleed and blister, set broken bones and cut off limbs.

Most states did not require a diploma, or even a license, to practice medicine; but with medical degrees so accessible, there was little reason for any aspiring doctor to go without one.36

John Harvey Kellogg

Thus in the fall of 1872 James White arranged with Merritt Kellogg, of the class of '68, to return to Florence Heights with four carefully chosen Battle Creek students: John Harvey Kellogg, a protégé of the Whites and Merritt's younger half-brother; Jennie Trembley, an editorial assistant with the Reformer; and the two White boys, Edson and Willie. For several years Ellen White had dreamed of Edson's becoming a physician, but he had turned out to be such a poor health reformer she had finally given up on him in despair. "To place you in a prominent position to prove you where a failure would be so apparent," she wrote of his medical ambitions, "would disgrace us and yourself also and discourage you." Nevertheless, when the opportunity came in 1872 for him to try his hand at doctoring, she gave her consent — provided that he rely principally on his own resources.37

The most promising of the four, and the one on whom the Whites were counting the most, was John Kellogg, the precocious son of J. P. Kellogg, an early Adventist health reformer. When John was only about twelve years old, James White had brought him to the Review and Herald Press to learn printing. In just a few years the lad had worked himself up from errand boy to typesetter and occasional editor and had read all the books and journals on health reform that he could get his hands on. Aiming to become a teacher, he had enrolled at age twenty in the Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti. During his second term there word reached him of the Whites' decision to sponsor him at Trall's medical school.38

The Hygeio-Therapeutic College proved to be just what James White had ordered: a doctor mill. Standards and staff alike were woefully inadequate. On opening day, when Trall found his faculty short two teachers (he had three on hand, including himself), he improvised by pressing Merritt into service as instructor in anatomy and John as lecturer on chemistry. The arrangement worked reasonably well until John innocently wandered onto the forbidden field of organic chemistry — a science Trall insisted did not exist — and was subsequently relieved of his duties. Throughout the term the Kellogg and White brothers shared a room but apparently not a love for medicine. According to Merritt, Edson and Willie seldom cracked a book and always went to bed as early as possible. They did, however, attend lectures and were thus able to spy on Trall for their mother, who was curious to know if the doctor picked her writings to pieces or questioned them in any way. Despite the fact that he never examined his students, and that some were not legally old enough to practice medicine, Trall awarded them each a handsome diploma and sent them out to ply their trade on an unsuspecting world.39

Since most of the Battle Creek students went into fields other than medicine, few patients in this instance suffered from Trall's lax standards. John Kellogg, the only one of the four to make a full-time career of medicine, wisely went on to study for two additional years at orthodox and reputable institutions: the College of Medicine and Surgery of the University of Michigan (1873-75) and the Bellevue Hospital Medical School in New York City (1874-75). Although his decision to attend Bellevue initially went against the "urgent advice" of James White, who "had the impression that so long as nature had to do the healing work anyway, it was quite unnecessary for the doctor to worry about so much minute detail," he eventually won the elder's moral and financial backing. Upon receiving his degree, five-foot, four-inch John proudly wrote Willie White that he now felt "more than fifty pounds bigger since getting a certain piece of sheepskin about two feet square. It's a bonafide sheep, too, by the way, none of your bogus paper concerns like the hygieo-therapeutic document."40

Young Kellogg had a right to be proud, for he had pulled himself up from his sectarian roots to become the first Seventh-day Adventist worthy of the title "doctor." In the spring of 1875 he returned to Battle Creek and joined the staff of the Western Health Reform Institute. Being politically astute and perhaps grateful — he at once allied himself with the Whites in their efforts to maintain control of an expanding church organization. That winter he joined Uriah Smith and Sidney Brownsberger, principal of the Adventist's Battle Creek College, in pledging to assist the Whites in bringing "discipline and order" to the work in Battle Creek. The alliance paid off handsomely the following year when the group secured his appointment, at age twenty-four, to the superintendency of the health institute, replacing Dr. William Russell, who left with over one-fourth of the patients to run a water cure in Ann Arbor. For the next four years Kellogg thrived as James White's "fair-haired boy," but he eventually came to resent the elder's dictatorial ways.41

Kellogg's fondest wish was to turn the poorly equipped Battle Creek water cure into a scientifically respectable institution where a wide variety of medical and surgical techniques would be used. In this task he found a ready and powerful ally in Ellen White, who was beginning to resent having "worldlings sneeringly [assert] that those who believe present truth are weak-minded, deficient in education, without position or influence." A first-rate medical center would prove her detractors wrong and bring fame and honor to Seventh-day Adventists. In several respects the time seemed propitious for such a move. A handful of Adventist young people were coming out of recognized medical schools, patients were flocking to the institute, and the old debts were finally off the books. So when Kellogg approached the prophetess with plans for a large multistoried sanitarium, he met a warm response. And when Ellen had a dream sanctioning the erection of a large building, it was all James needed to volunteer to raise the necessary funds. "Now that we have men of ability, refinement, and sterling sense, educated at the best medical schools on the continent," he wrote glowingly in the Review and Herald, "we are ready to build."42

By the spring of 1878 an imposing new Medical and Surgical Sanitarium stood on the old institute grounds. But the Whites were not pleased. Construction costs had once again plunged the church heavily into debt and disturbed the tranquillity of Elder and Mrs. White. She had originally called for a first-class medical institution, but now that the building was finished, it reminded her of "a grand hotel rather than an institution for the treatment of the sick." Out went a testimony reprimanding the prodigal sanitarium managers for their "extravagant outlay" in "aiming at the world's standards," and for other misdeeds. Although Kellogg felt some of the charges leveled against him were grossly unfair, he attributed the outburst more to the machinations of James than to Ellen herself. In the fall of 1880 he retaliated by uniting with two of James White's rivals, Elders S. N. Haskell and G. I. Butler, to force the aging leader off the sanitarium board and to elect Haskell chairman in his place. Within a year James White lay dying in Battle Creek as a reconciled Dr. Kellogg labored in vain to save the patriarch's life.43

Through the following years Kellogg struggled to escape his sectarian past by identifying with the "rational medicine" of such distinguished practitioners as Jacob Bigelow and Oliver Wendell Holmes. The "rational" physician, said Kellogg, adopts "all of hygieo-therapy and all the good of every other system known or possible," not just the water cure. His ties to hydropathy were too strong to sever entirely, however; and in the mid-1880s local physicians, led by a former student and associate, Dr. Will Fairfield, tried (unsuccessfully) to oust him from the county medical society for sectarianism. Kellogg's vindication came sometime later when Dr. Henry Hurd, medical director of the Johns Hopkins University Hospital, publicly lauded him for "having converted into a scientific institution an establishment founded on a vision." But even after he had become a national figure, and his sanitarium world famous, Kellogg never forgot that the institution's "real founder and chief promoter" was Ellen White.44

Footnotes

- EGW, Health; or, How to Live (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1865), no. 3, p. 59.

- EGW, "Health Reform Principles" (MS-86-1897), in Selected Messages from the Writings of Ellen G. White (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1958), II, 290.

- EGW to Bro. and Sister Lockwood, September [14], 1864 (L-6-1864, White Estate); [Uriah Smith], "The Health-Reform Institute," R&H, XXVIII (July 10, 1866), 48. The Review and Herald was outspokenly critical of President Andrew Johnson, whom they openly called "a rebel and traitor." See R&H, XXVII (February 27, 1866), 104.

- D. E. Robinson, The Story of Our Health Message (3rd ed.; Nashville: Southern Publishing Assn., 1965), pp. 144-52; "The Western Health-Reform Institute," R&H, XXVIII (June 19, 1866), 24; J. N. Loughborough, "Report from Bro. Loughborough," ibid., XXVIII (September 11, 1866), 117.

- D. T. Bourdeau, "The Health Reform," R&H, XXVIII (June 12, 1866), 12; Loughborough, "Report," p. 84.

- "The Western Health-Reform Institute," R&H, XXVIII (June 19, 1866), 24; "The Western Health Reform Institute," ibid., XXVIII (August 7, 1866), 78. See Loughborough, "Report," p. 117, for a reply to complaints of excessive prices.

- Ibid.; I. D. Van Horn, "Another Standard Bearer Fallen," ibid., LXXVII (March 13, 1900), 176; W. C. White, "The Origin of the Light on Health Reform among Seventh-day Adventists," Medical Evangelist, XX (December 28, 1933), 2.

- EGW to Dr. and Mrs. Lay, May 6, 1867 (L-6-1867, White Estate); EGW to Bro. and Sister Lockwood, September [14], 1864; J. H. Kellogg, "Christian Help Work," General Conference Daily Bulletin, I (March 8, 1897), 309; "Constitution of the N.H.R. Association," Laws of Life, VIII (August, 1865), 126; C. B. Burr (ed.), Medical History of Michigan (Minneapolis: Bruce Publishing Co., 1930), I, 641. Lay's graduation from the Detroit Medical College (now the Wayne State University of Medicine) is verified in a letter to the author from Mary E. McNamara, March 14, 1973.

- "Items for the Month," HR, I (February, 1867), 112; Diary of Mrs. Angeline S. Andrews, entry for January 2, 1865 (C. Burton Clark Collection); EGW to Edson White, November 9, 1867 (W-14-1867, White Estate); R. T. Trall, "Visit to Battle Creek, Mich.," HR, III (July, 1868), 14. The original institute staff seems to have been composed of three "doctors": Lay, Lamson, and John F. Byington, son of the first General Conference president. William Russell joined the staff in the fall of 1867; and in the next few years J. H. Ginley and Mary A. Chamberlain also connected with the institute. Except for the two women, who briefly attended Trall's hydropathic college (Mrs. Chamberlain at some time in her life also graduated from the homeopathy course at the University of Michigan), none of these individuals seems to have had formal medical training. For obituaries of Byington, Chamberlain, and Ginley, see R&H, XL (June 25, 1872), 5; ibid., LXXVII (April 17, 1900), 256; and ibid., LXXXI (February 4, 1904), 23.

- "Fourth Annual Session of General Conference," R&H, XXVIII (May 22, 1866), 196; "Prospectus of the Health Reformer," ibid., XXVIII (June 5, 1866), 8. For Lay's "Health" series, see ibid., XXVI (July 4, 1865), 37; (July 25, 1865), 61; (August 15, 1865), 85; (September 12, 1865), 117.

- EGW, "Duty to Know Ourselves," HR, I (August, 1866), 2-3; EGW, "The Health Reformer," Testimonies, I, 552.

- J. F. Byington, "The Health Institute," R&H, XXIX (January 1, 1867), 43; G. W. Amadon, "My Experiences in Health Reform," HR, III (February, 1869), 149; Isaac Sanborn, "My Experience," ibid., I (January, 1867), 84.

- [H. S. Lay], "Items for the Month," HR, I (September, 1866), 32; J. F. Byington, "The Greatest Humbug of the Age," ibid., III (May, 1869), 209; E[llen] G. W[hite], "Florence Nightingale," ibid., VI (July, 1871), 27; J[ames] W[hite], "The Health Reformer," ibid., V (January, 1871), 142. For a recent discussion of reforms in regular medicine, see William G. Rothstein, American Physicians in the 19th Century: From Sects to Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972), p. 181.

- H. S. Lay, "What Shall Be Done?" R&H, XXIX (January 8, 1867), 54. On the GC budget, see R&H, XXVII (May 22, 1866), 196; and R&H, XXIX (January 1, 1867), 48.

- [Uriah Smith], "The Health Reform Institute," ibid., XXIX (January 29, 1867), 90; Uriah Smith to EGW, February 5, 1867 (White Estate).

- Ibid.

- EGW, "The Health Reform," Testimonies, I, 485-95.

- "Meeting of the Health Reform Institute," R&H, XXIX (May 28, 1867), 279; E. S. Walker, "$15,000 Wanted Immediately," ibid., XXX (August 27, 1867), 168-69.

- EGW to Brother Aldrich, August 20, 1867 (A-8-1867, White Estate); EGW, "The Health Institute," Testimonies, I, 558-60.

- Ibid., I, 559-64; D. M. Canright, Life of Mrs. E. G. White, Seventh-day Adventist Prophet: Her False Claims Refuted (Nashville: B. C. Goodpasture, 1953), pp. 77-78. Canright errs in implying that Mrs. White wrote Testimony No. 12 to justify her husband's tearing down of the sanitarium building.

- E. S. Walker to James White, September 24, 1867 (White Estate). In this letter the institute directors offer to buy some property from the Whites for six thousand dollars at 7 percent interest if James White will agree "to cooperate with us in raising means to pay for your place and to erect and inclose the new building at as early a day as possible."

- "Interview between Geo. W. Amadon, Eld. A. C. Bourdeau, and Dr. J. H. Kellogg, October 7, 1907," p. 88 (Ballenger-Mote Papers). The "old-timer" mentioned was Amadon. James White may not have been consulted about plans for the new building, and he was absent the morning General Conference delegates voted to enlarge the institute; but he did attend the 1867 General Conference session and certainly was aware of plans for a new building before construction began. James White, "The Conference," R&H, XXIX (May 28, 1867), 282; "Business Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Session of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists," ibid., pp. 283-84.

- EGW to Edson and Emma White, November 15, 1871 (W-15-1871, White Estate); EGW, "The Work at Battle Creek," Testimonies, III, 89; James White, "The Health Institute," R&H, XXXI (June 16, 1868), 408-9.

- EGW, "The Health Institute," Testimonies, I, 633-43. For the persistent use of First-day, etc., see the masthead of the Review and Herald.

- J. N. Andrews, "Amusements," HR, I (December, 1866), 80; O. F. Conklin, "Thanksgiving at the Health-Reform Institute," ibid., pp. 74-75; EGW, "The Health Institute," Testimonies, I, 633-43; EGW, "Questions and Answers," R&H, XXX (October 8, 1867), 261.

- EGW, "The Health Institute," Testimonies, I, 634; EGW, "The Health Institute," ibid., III, 165-85; EGW to Dr. and Mrs. Lay, February 13, 1870 (L-30-1870, White Estate); "Second Annual Meeting of the Health Reform Institute," R&H, XXXI (May 26, 1868), 258; "The Health Reform Institute," R&H, XXXIII (May 25, 1869), 175; "Health Institute," R&H, XXXV (May 3, 1870), 160; Gerald Carson, Cornflake Crusade (New York: Rinehart & Co., 1957), p. 82. This was not a happy time for the Whites. Criticism of their conduct reached such proportions that in 1870 the church felt it necessary to publish a 112-page Defense of Eld. James White and Wife: Vindication of Their Moral and Christian Character (Battle Creek: SDA Publishing Assn., 1870), countering charges of misusing funds, illicit sex, and other "shameful slanders."

- James White, "Report of Meetings," R&H, XXXI (April 28, 1868), 312.

- James White, "Report from Bro. White," ibid., XXXI (May 5, 1868), 328; J. N. Andrews, "Business Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Session of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists," ibid., XXXI (May 26, 1868), 356; M. G. Kellogg to EGW, July 16, 1868 (White Estate); "Acknowledgment," R&H, XXXII (August 18, 1868), 137. In the 1870s Merritt Kellogg authored at least two books on health reform: The Bath: Its Use and Application (Battle Creek: Office of Health Reformer, 1873), and The Hygienic Family Physician: A Complete Guide for the Preservation of Health, and the Treatment of the Sick without Medicine (Battle Creek: Office of the Health Reformer, 1874).

- J. N. Andrews and Others, "Lectures by Dr. Trall," R&H, XXXI (May 26, 1868), 360; R. T. Trall, "Visit to Battle Creek, Mich.," p. 14; [R. T. Trall], "Dress Reform Convention," HR, IV (September, 1869), 57. Dr. Jackson had been invited to lecture in Battle Creek in March of 1866, but a death at Dansville forced a cancellation; "Lectures at Battle Creek," Laws of Life, IX (March, 1866), 43; and "Going to Battle Creek," ibid., IX (April, 1866), 58.

- J. N. Loughborough, The Great Second Advent Movement: Its Rise and Progress (Washington: Review and Herald Publishing Assn., 1905), pp. 364-65.

- James White, "The Health Reformer," R&H, XXXII (July 28, 1868), 96; R. T. Trall, "Change of Programme," HR, III (July, 1868), 14.

- EGW, "An Appeal for Burden-Bearers," Testimonies, III, 19-21. The managing editor, William C. Gage, later served as a temperance mayor of Battle Creek.

- [James White], "The Health Reformer," HR, V (June, 1871), 286; [James White], "Close of the Volume," ibid., VII (December, 1872), 370; James White, "Health Reform No. 5: Its Rise and Progress among Seventh-day Adventists," ibid., V (March, 1871), 190; [James White], "The Health Reformer," ibid., V (March, 1871), 172; "Hygienic Institute Nursery," ibid., V (June, 1871), 298; EGW, "Our Late Experience," R&H, XXVII (February 27, 1866), 97.

- [James White], "Close of the Volume," p. 370; [J. H. Kellogg], "Hygieo-Therapy and Its Founder," Good Health, XVII (March, 1882), 92.

- James White to G. I. Butler, July 13, 1874 (White Estate).

- Thomas L. Nichols, Forty Years of American Life (London: John Maxwell and Co., 1864), I, 363-64. See also William Frederick Norwood, Medical Education in the United States before the Civil War (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944), pp. 396-406.

- M. G. Kellogg, memoir dictated to Clara K. Butler, October 21, 1916 (Kellogg Papers, MHC). On Edson's medical aspirations, see the following letters in the White Estate: EGW to Edson White, December 29, 1867 (W-21-1867); EGW to Edson White, June 10, 1869 (W-6-1869); EGW to Edson and Emma White, n.d. (W-14-1872); and EGW to Edson and Willie White, February 6, 1873 (W-6-1873).

- Richard W. Schwarz, "John Harvey Kellogg: American Health Reformer" (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1964), pp. 17-22, 113-14.

- M. G. Kellogg, memoir dictated to Clara K. Butler, October 12, 1916; EGW to Edson and Willie White, February 6, 1873; [J. H. Kellogg], "Hygieo-Therapy and Its Founder," p. 92. The entire M. G. Kellogg memoir is reproduced in Ronald L. Numbers, "Health Reform on the Delaware," New Jersey History, XCII (Spring, 1974), 5-12.

- J. H. Kellogg, "My Search for Health," MS dated January 16, 1942 (Kellogg Papers, MHC); J. H. Kellogg to Willie White, March 3, 1875, and April 12, 1875 (White Estate); Richard W. Schwarz, John Harvey Kellogg, M.D. (Nashville: Southern Publishing Assn., 1970), p. 60. A friend of Kellogg's at Bellevue, and the only other health reformer, was Jim Jackson, son of the founder of Our Home; see Kellogg, "My Search for Health," p. 9; and Kellogg to Willie White, March 3, 1875.

- Schwarz, "John Harvey Kellogg: American Health Reformer," pp. 174-77.

- [J. H. Kellogg], "The Health Institute," HR, X (June, 1875), 192; EGW, Testimony for the Physicians and Helpers of the Sanitarium (n.d. [1880 ?]), p. 8; J. H. Kellogg, autobiographical memoir, October 21, 1938 (Kellogg Papers, MHC); J[ames] W[hite], "Home Again," R&H, XLIX (May 24, 1877), 164.

- "Interview between Geo. W. Amadon, Eld. A. C. Bourdeau, and Dr. J. H. Kellogg," pp. 88-89; EGW, Testimony for the Physicians and Helpers of the Sanitarium, pp. 52-55; Schwarz, "John Harvey Kellogg: American Health Reformer," p. 177. When this testimony was reprinted for general circulation, Kellogg's name and several criticisms were deleted; see EGW, Testimonies, IV, 571-74.

- J. H. Kellogg, "The American Medical Missionary College," Medical Missionary, V (October, 1895), 291; [J. H. Kellogg], "Hygieo-Therapy and Its Founder," p. 93; J. H. Kellogg to EGW, December 19, 1885, December 6, 1886, and October 30, 1904 (White Estate). Hurd is quoted in J. H. Kellogg, autobiographical memoir, October 21, 1938, p. 5.